Quick Guide

- What Exactly Are We Trying to Prevent? Understanding Diving Accidents

- The Golden Rules: Your Pre-Dive Prevention Foundation

- The Dive Plan: Your Underwater Roadmap

- During the Dive: The Prevention Mindset in Action

- When Things Go Sideways: Managing Problems Before They Become Accidents

- Post-Dive: Prevention Isn't Over When You Surface

- Answering Your Real Questions About Diving Accident Prevention

Let's be real for a second. When most of us think about scuba diving, we're picturing the amazing stuff – the weightlessness, the colors, the quiet, that turtle you finally got a good photo of. We're not usually picturing things going wrong. But here's the thing I've learned after more dives than I can count: the divers who have the most fun, who see the coolest stuff year after year, are the ones who take diving accident prevention dead seriously. It's not about being scared. It's about being smart. It's the ticket that lets you keep doing this thing you love.

I remember my first real scare. It wasn't dramatic, no Hollywood music. It was a slow creep of confusion at 20 meters, a slight headache that felt... off. My buddy was a bit ahead, distracted by a nudibranch. That moment, that quiet, personal "uh-oh," taught me more than any manual. Prevention isn't just a checklist. It's a mindset you carry from the parking lot to the depth and back again.

What Exactly Are We Trying to Prevent? Understanding Diving Accidents

Before we can prevent something, we need to know what it looks like. A "diving accident" isn't just a shark attack (which, let's be clear, is incredibly rare despite what TV says). It covers a range of incidents, most of which are far more mundane but just as dangerous.

The big ones the pros talk about include Decompression Sickness ("the bends"), lung over-expansion injuries, drowning, and equipment-related failures. Then you've got the secondary issues that can lead to the big ones: running out of air, getting separated from your buddy or boat, strong currents, and marine life injuries (more often from urchins or fire coral than sharks).

What does the data say? Organizations like the Divers Alert Network (DAN) spend their lives tracking this stuff. Their annual reports consistently show that the root causes are rarely mysterious. They're things like inadequate buoyancy control, poor gas management (that's fancy talk for watching your air), insufficient pre-dive planning, and pushing beyond personal limits. It's human stuff, not monster stuff.

See the pattern? It's mostly about decisions, not demons.

The Golden Rules: Your Pre-Dive Prevention Foundation

This is where it all starts, on dry land. A good dive is made before you even get wet. Skipping these steps is like building a house on sand – it might look okay until the first wave hits.

Get Properly Trained and Stay Current

This seems obvious, right? But you'd be surprised. I've met divers using advanced techniques they learned from a YouTube video. Terrifying. A recognized agency like PADI, SSI, or NAUI doesn't just give you a card; they give you a framework for survival. Their protocols exist for a reason.

And it doesn't stop after the open water course. If you haven't dived in a year, a refresher isn't a sign of weakness; it's a sign of intelligence. Skills get rusty. A good Scuba Review with an instructor rebuilds confidence and muscle memory. Think of it as an investment in all your future fun.

The Medical Check: The Conversation Nobody Wants to Have

Filling out the medical form isn't a suggestion. Some divers treat it like a nuisance, scribbling "no" down the whole column without thinking. That's a gamble with very high stakes. Conditions like asthma, heart issues, diabetes, or even a recent cold can have serious consequences under pressure.

Be brutally honest with yourself and your doctor. If there's a question, get a sign-off from a physician who understands dive medicine. The DAN Medical Statement is a great, clear resource. This isn't about being barred from diving; it's about knowing your personal parameters for safe diving. A managed condition is often a green light. A hidden one is a ticking clock.

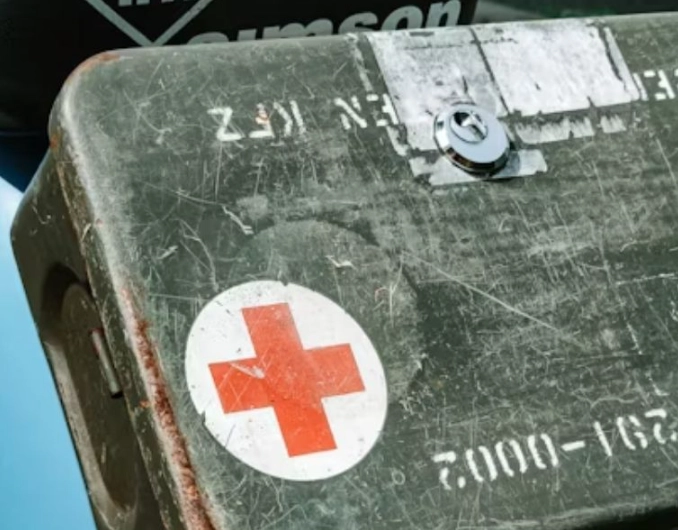

Gear: Your Life Support System

Your gear is the only thing between you and the ocean. Trusting it blindly is a recipe for trouble. Diving accident prevention starts with your equipment checklist.

Pre-Dive Check (The BWRAF Buddy Check): This is non-negotiable. Every. Single. Dive. BCD, Weights, Releases, Air, Final OK. It takes 90 seconds and has caught countless problems. I use my own mnemonic: "Big Whales Rarely Attack Fish" – same steps, just sticks in my head. Find what works for you, but do it.

Rental Gear Inspection: Don't just assume it's good. Look for cracks, fraying, excessive corrosion. Inhale from the regulator – does it breathe smoothly or feel like sucking a thick milkshake? Test the inflator/deflator on the BCD. Does it hold air? A quick check of the tank's visual inspection sticker (the VIP) tells you it's been looked at recently.

| Gear Piece | What to Check For | Red Flag |

|---|---|---|

| Regulator | Second-stage freeflow, hose cracks, firm mouthpiece | Hissing when not in mouth, brittle/rubbery hoses |

| BCD | Holds inflation, deflates fully, all dumps work | Slow leaks, stuck inflator button, corroded buckle |

| Mask & Fins | Strap condition, skirt integrity, fin strap/buckle | Cracked lens, torn skirt, broken fin buckle |

| Dive Computer | Powers on, battery OK, settings correct (gas, conservatism) | Low battery warning, last dive data from 2020, wrong gas mix set |

| Exposure Suit | Zippers work, no major tears, proper fit | Large holes letting water flush through, broken zipper |

See? It's not rocket science. It's just attention. And while we're on gear, servicng. Your own regs and BCD need annual professional servicing. It's a cost, sure, but it's cheaper than a hospital bill. A friend learned this the hard way when his unserviced octopus freeflowed at depth, spooking him into a rapid ascent. Not worth it.

The Dive Plan: Your Underwater Roadmap

Jumping in with a vague idea of "going down there" is asking for trouble. A good plan is the backbone of diving accident prevention.

You and your buddy need to agree on:

- Maximum Depth and Time: Stick to the shallower of your computers' no-deco limits. The ocean isn't going anywhere. There's always another dive.

- Air Management: The rule of thirds? The rule of quarters? Pick one and use it. (Turn the dive when you hit half your starting air? That's for very conservative or overhead environments; for open water, turning at 1/3 or 1/2 of your starting pressure is common). More importantly, agree on your turn pressure and your "head for the surface" pressure (like 70 bar/1000 PSI).

- Route and Communication: Which way are we going? What hand signals will we use? What's the procedure if we get separated? (Hint: search for a minute, then safely surface).

- Emergency Procedures: Briefly review: lost buddy, low air, freeflow, entanglement. A quick mental run-through makes real reactions faster.

During the Dive: The Prevention Mindset in Action

This is where the rubber meets the road. All your planning leads to these moments.

Buddy System: It's Not Just a Suggestion

Your buddy is your backup brain and air supply. Stay close enough to make eye contact easily. Check on each other frequently – a thumbs-up, an air gauge check. I make it a habit to glance at my buddy's exhaust bubbles every minute or so. Regular bubbles? They're breathing. No bubbles? Time to get their attention, fast.

What ruins the buddy system? Underwater photographers, I'm looking at you (and I include myself here). It's so easy to get tunnel vision on a subject. The best diving accident prevention tip for photographers: shoot, then immediately look up, find your buddy, re-orient. Rinse and repeat. Your buddy's job is to stay with you, not chase you around a reef.

Buoyancy Control: The Master Skill

Poor buoyancy isn't just bad for the reef; it's a direct path to accidents. Bouncing off the bottom stirs up silt (reducing visibility), damages marine life, and wastes air. Bobbing up and down uncontrollably increases your risk of lung over-expansion or decompression sickness.

Good buoyancy means you're calm, air-efficient, and in control. You can stop on a dime to deal with a problem. You're not fighting the water. How do you get it? Practice in a pool or shallow, sandy area. Master your breathing – small sips of air in and out, using your lungs as your primary fine-tuner. A perfectly weighted diver will hover motionless at a safety stop with an almost empty BCD and half a breath in their lungs.

It feels like flying. And it's the safest way to dive.

Monitoring and Awareness: Your Personal Dashboard

You need to develop a constant, gentle scan of your personal dashboard: depth, time, air, no-deco time, and buddy. Don't fixate on any one thing, but let your eyes roam over them every minute or two. Modern computers make this easy with big, clear displays.

But also scan your body. How do you feel? A little tired? More out of breath than usual? A weird itch or joint pain? Listen to those signals. They're your early warning system. The mantra here is: "If in doubt, call it out." End the dive. There is no shame in a short, safe dive. The shame is in pushing through a warning sign and needing a rescue.

Ascent and Safety Stop: The Non-Negotiable Finish

This is arguably the most critical phase for diving accident prevention. A slow, controlled ascent is your best defense against decompression sickness. Your computer will give you a rate – often 9-10 meters/30 feet per minute. That's SLOWER than you think. Follow it.

And the safety stop. Three minutes at 5 meters/15 feet. It's not just for "safety"; it's a mandatory decompression step for any dive below 10 meters. Hang there. Look at your computer. Breathe normally. This is your body's chance to off-gas excess nitrogen in a controlled environment. Skipping it to get back to the boat 180 seconds faster is the ultimate false economy.

When Things Go Sideways: Managing Problems Before They Become Accidents

Even with perfect prevention, small issues arise. How you handle them determines if they stay small.

- Low on Air: Signal your buddy immediately. Don't wait until you're in the red. Ascend together calmly, performing your safety stop if possible. Your buddy's octopus is there for a reason.

- Buddy Separation: Search for no more than one minute while slowly turning 360 degrees. If you don't find them, make a safe, controlled ascent to the surface. Look around there. This is why the pre-dive plan includes a surface meeting point.

- Entanglement: Stop. Don't thrash. Breathe. Signal your buddy. Often, they can see the problem clearly and free you. If alone, work slowly and methodically. A cutting device (shears or a line cutter) on your BCD shoulder strap is a lifesaver. Literally.

- Freeflowing Regulator: It's loud and startling. Don't panic. You can still breathe from it by putting your mouth to the side of the mouthpiece. Or, simply switch to your alternate air source (octopus). Signal your buddy, and begin a controlled ascent. The key is not to hold your breath as you ascend with expanding air in your lungs.

The common thread in all these responses? Stop. Breathe. Think. Act. Panic is the real enemy, not the problem itself. Training and mental rehearsal make these responses automatic.

Post-Dive: Prevention Isn't Over When You Surface

Your responsibility for diving accident prevention continues on the boat or the beach.

Hydrate. Diving is dehydrating. Drink water, not just beer or soda. Dehydration thickens your blood and is a known risk factor for decompression sickness.

Watch for Symptoms. Know the signs of DCS: unusual fatigue, itchy skin, joint pain, dizziness, weakness, numbness, or a rash. Symptoms can appear hours later. If you feel "off" after a dive, don't brush it off. The Divers Alert Network emergency hotline is +1-919-684-9111. Have it saved in your phone. Their doctors are there 24/7 to give advice. Calling them with a vague worry is always, always the right move.

Log Your Dive. Not just for stamps. Note how you felt, what your air consumption was, any issues with gear or conditions. This log becomes a personal safety record, helping you spot patterns over time.

Answering Your Real Questions About Diving Accident Prevention

What's the #1 most common cause of diving accidents?

If you had to pin it down, it's running out of air or being low on air, which then triggers a chain of bad decisions, often a panicked, rapid ascent. This is why air management is drilled into you from day one. It's the most fundamental rule. Check your gauge, often.

How likely am I to get "the bends"?

On recreational dives following standard no-decompression limits and safe ascent rates? The risk is very low. But it's not zero. The risk increases when you push limits, skip safety stops, dive dehydrated, or make multiple deep dives over several days. Respect the tables/computer, and the odds are heavily in your favor.

Is it safe to dive alone? Some experts do it.

This is a hot topic. Solo diving requires specialized training, redundant gear (two completely independent breathing systems), and a very different mindset. For 99% of recreational divers, the answer is a firm no. The buddy system is your primary redundant system. The "experts" you hear about have trained for years for that specific scenario. It's not something to try because it seems cool or independent.

I'm a bit claustrophobic. Will that cause an accident?

Not necessarily. Many divers manage mild claustrophobia. The key is honesty and control. Start in very calm, clear, shallow water. Focus on your breathing. Look out into the blue, not at what's "enclosing" you. If you feel panic rising, stop, hold onto something stable, and breathe slowly until it passes. Communicate this to your instructor or buddy. Forcing yourself through a full-blown panic attack underwater is extremely dangerous. Know your triggers.

How often does gear actually fail?

Modern, well-maintained scuba gear is incredibly reliable. Catastrophic failure is rare. More common are minor annoyances that become problems if ignored: a slow O-ring leak, a fin strap about to break, a sticky inflator button. This is why pre-dive checks and annual servicing are so critical. They catch the "about-to-fail" stuff.

So go ahead. Plan that next dive. Check your gear like your life depends on it (because it does). Brief your buddy like you mean it. Descend calmly, breathe slowly, and look around in wonder. That feeling of awe and freedom? That's what all this prevention protects. It's not a set of rules meant to spoil your fun. It's the guardrail on the mountain road that lets you enjoy the view without fear.

See you down there. Safely.

Your comment