What You’ll Find in This Deep Dive

- The Core Problem: When the Partnership Shatters

- The Primary Culprit: Thermal Stress from Ocean Warming

- The Local Stressors: Pollution and Poor Water Quality

- Other Physical and Biological Stressors

- Diagnosing the Cause: It's Rarely Just One Thing

- So, What Can Actually Be Done?

- Common Questions People Are Still Asking

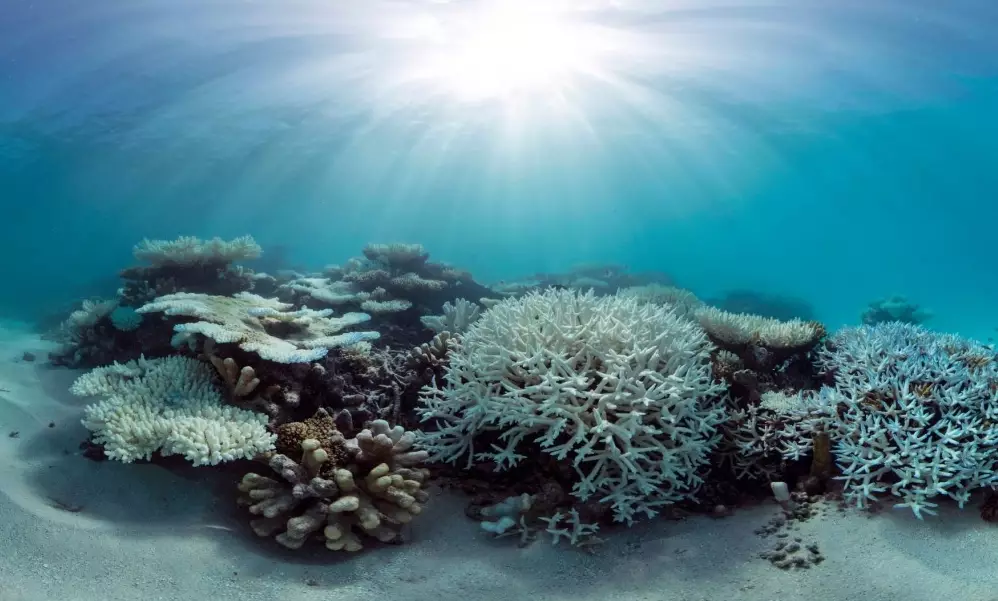

You've probably seen the photos. Stunning underwater landscapes transformed into ghostly white graveyards. Coral bleaching is that stark, alarming signal that something's seriously wrong down there. But if you think it's just about the water getting a bit too warm, you're only seeing the tip of the iceberg. The full story of what causes coral bleaching is more complicated, and honestly, more worrying.

I remember the first time I saw a bleached coral in person. It was on a dive years ago, and the guide pointed to a large brain coral that was this bright, almost glowing white. "It's stressed," he said simply. At the time, I didn't really get it. Stress? Like how I feel before a deadline? It seemed like an odd word for a marine animal. But that's the key—corals are animals, incredibly complex ones living in a tight, mutually beneficial partnership. And when that partnership breaks down, you get bleaching. Let's peel back the layers on what really causes this to happen.

The Core Problem: When the Partnership Shatters

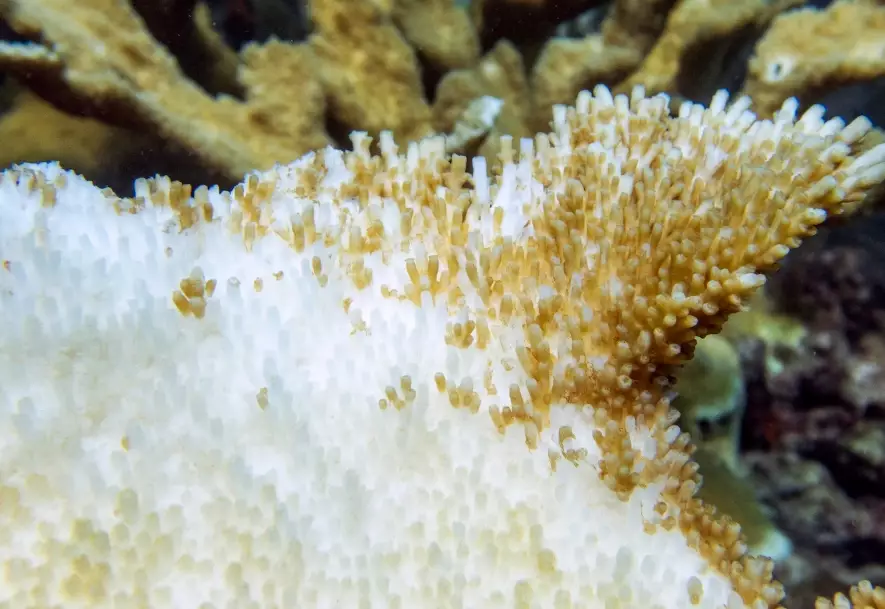

At its heart, coral bleaching is a divorce. It's the breakdown of the symbiotic relationship between the coral animal (the polyp) and its photosynthetic algae (the zooxanthellae). These algae give corals their color and most of their energy. When corals get stressed—and here's the critical part about what causes coral bleaching—they essentially evict their algal roommates. Without the algae, the coral's translucent tissue reveals its white limestone skeleton underneath. It's not dead immediately, but it's starving, severely weakened, and highly susceptible to disease.

So, what stresses them out enough to break this billion-year-old partnership? The stressors fall into a few big buckets, and they often work together like a one-two punch.

The Primary Culprit: Thermal Stress from Ocean Warming

Let's not beat around the bush. The number one driver of mass, global bleaching events is elevated sea surface temperatures. This isn't speculation; it's the overwhelming consensus from decades of research by institutions like NOAA's Coral Reef Watch. When water temperatures stay even 1°C above the usual summer maximum for a week or more, corals start to bleach.

Why is heat so bad? It disrupts the photosynthetic machinery inside the zooxanthellae. Think of it like forcing a factory worker to operate machinery in a sweltering, overheated room. Efficiency plummets, and toxic by-products (reactive oxygen species) start to build up. These toxins damage both the algae and the coral host. To save itself, the coral expels the algae. It's a desperate survival move with a high cost.

The scary trend? These heatwaves are becoming more frequent, intense, and longer-lasting due to climate change.

It's not just the absolute temperature, either. It's the rate of change. A rapid spike is more dangerous than a slow climb. And it's the duration. A single hot day might not do it, but weeks of anomalous warmth—what scientists call "Degree Heating Weeks"—is a death sentence for many reefs. The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority has documented this brutal pattern in recent mass bleaching events.

Sunlight Intensity: The Heat Amplifier

This one is tightly linked to heat. High solar irradiance, especially UV radiation, supercharges the heat stress. A hot, still, sunny day is the worst-case scenario. The UV rays directly damage the algal cells and compound the production of those harmful toxins. You'll often see the tops of corals, which get the most sun, bleach first, while shaded sides or corals in deeper, cooler water hold on longer. This is a key clue when you're trying to diagnose what causes coral bleaching on a specific reef—pattern matters.

The Local Stressors: Pollution and Poor Water Quality

This is where the story gets more nuanced, and where local action can actually make a difference. While we can't fix global ocean temperatures overnight, cleaning up our local waters is something communities can tackle. These factors might not initiate a global event, but they make corals far more vulnerable when a heatwave hits.

Nutrient Runoff: The Silent Weakener

Fertilizers from farms, sewage discharge, and urban runoff wash nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into coastal waters. You'd think more nutrients are good, right? Not in a coral reef ecosystem. This causes algal blooms (the slimy, macroalgae kind) that smother corals and compete for space. More insidiously, it shifts the delicate balance inside the coral's own system. Excess nutrients can actually make the zooxanthellae multiply too much inside the coral, creating an unstable relationship that collapses at the slightest hint of thermal stress. It's like overloading the system until it's brittle.

Sedimentation: Suffocating the Polyps

Dredging, coastal construction, and deforestation can dump huge amounts of silt and sediment into the water. This clouds the water, blocking the sunlight the zooxanthellae need to photosynthesize. Even worse, fine sediments can physically settle on the corals. The coral has to spend precious energy cleaning itself—energy it should be using for growth and repair. If the sediment is thick enough, it can literally smother the polyps. I've seen reefs near construction sites that look like they're covered in a layer of grey mud. They're the first to go when temperatures rise.

Chemical Pollution: Sunscreen and Beyond

This one gets a lot of press, particularly chemicals like oxybenzone and octinoxate found in some sunscreens. Studies, including those summarized by the U.S. National Park Service, show these chemicals can induce bleaching, damage coral DNA, and disrupt reproduction even in tiny concentrations. Is it the biggest global cause? No. But in highly trafficked tourist areas, it's a significant localized stressor that's completely preventable. Other chemicals, from pesticides to heavy metals, add to the toxic cocktail.

Other Physical and Biological Stressors

The list doesn't end there. Sometimes, what causes coral bleaching is a direct physical assault.

Extreme low tides that leave corals exposed to the air and sun can cause rapid, localized bleaching. Freshwater inundation from heavy rains or flood plumes lowers salinity, shocking the corals. Diseases can also cause bleaching-like symptoms as they attack the coral tissue or the algae themselves. And then there's ocean acidification—the other big climate change threat. While it doesn't cause bleaching directly by weakening the skeleton-building process, it leaves corals more fragile and less able to recover from a bleaching event. It's a chronic stressor that erodes their long-term health.

Myth vs. Fact: A Quick Reality Check

Myth: A bleached coral is always dead.

Fact: It's in critical condition but can recover if the stress is removed quickly and algae return. Recovery takes years of good conditions, though.

Myth: Only climate change causes bleaching.

Fact: Climate change is the major amplifier, but local pollution makes reefs far more susceptible. Tackling both is non-negotiable.

Myth: All corals bleach at the same rate.

Fact: Some species are much more tolerant than others. Fast-growing branching corals are often the first to bleach and die, while massive boulder corals might withstand more stress.

Diagnosing the Cause: It's Rarely Just One Thing

When you see a bleached reef, you're usually looking at a combination of factors. Scientists are detectives, looking for patterns. Is the bleaching widespread across many species and depths? That points strongly to thermal stress. Is it patchy, affecting mainly shallow corals or those near a river mouth? That implicates local factors like sun exposure or runoff.

This table breaks down how to think about the different actors in this crisis:

| Stress Factor | How It Causes Bleaching | Geographic Scale | Key Identifier / Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated Sea Temperature | Disrupts photosynthesis, causes toxin buildup, forces coral to expel algae. | Regional to Global (Mass Events) | Widespread across depths & species; follows satellite heat anomaly maps. |

| High Solar/UV Radiation | Amplifies heat damage, directly damages algal cells. | Local to Regional | Bleaching most severe on sun-exposed surfaces (tops, upper sides). |

| Nutrient Pollution | Weakens symbiosis, promotes algal overgrowth, reduces coral resilience. | Local (Near coasts, watersheds) | Often coincides with macroalgae blooms; corals appear less robust before bleaching. |

| Sedimentation | Smothers polyps, blocks light, drains energy for cleaning. | Local (Near dredging/erosion) | Corals covered in fine sediment; high turbidity in water. |

| Chemical Pollutants | Direct toxicity to coral or algae; disrupts biological functions. | Local (Marinas, tourist sites) | Patchy in high-human-activity areas; can affect reproduction. |

| Freshwater Input | Drastic change in salinity (osmotic shock) stresses coral. | Local (After storms/floods) | Bleaching in nearshore areas following heavy rainfall or river discharge. |

See how they layer? A reef already struggling with murky water and fertilizer runoff has a much lower survival chance when a marine heatwave rolls in. That's why understanding the full spectrum of what causes coral bleaching is so important for conservation. You have to address the local weaknesses to buy time against the global threat.

So, What Can Actually Be Done?

It's easy to feel helpless. The scale is enormous. But framing the problem accurately shows us where the levers are. The path forward requires action at every level.

The Global, Non-Negotiable Action: Drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions to curb ocean warming and acidification. This is the ultimate solution to the primary driver of mass bleaching. Supporting policies and technologies that move us toward a low-carbon economy is foundational.

The Local & Regional Action (Where we have direct control):

- Improve Water Quality: Upgrade wastewater treatment, manage agricultural runoff with buffer zones, enforce regulations on coastal development and dredging. Clear water is resilient water.

- Protect Reef Ecosystems: Establish and properly manage Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) to reduce other stresses like overfishing. Healthy fish populations, especially herbivores that eat smothering algae, help reefs recover.

- Make Smart Consumer Choices: Use mineral-based (zinc oxide, titanium dioxide) sunscreens labeled "reef-safe." Be mindful of fertilizer use on your lawn. Support sustainable seafood and tourism operators.

- Support Restoration Science: Organizations are working on coral gardening, breeding heat-tolerant corals, and assisted evolution. This isn't a silver bullet, but it's a critical stopgap to preserve genetic diversity.

The goal isn't just to save pretty diving spots.

Reefs protect coastlines from storms, support fisheries that feed millions, and drive tourism economies. The cost of letting them die is astronomical, both ecologically and economically.

Common Questions People Are Still Asking

Can corals adapt or acclimate to warmer water?

There's some evidence of hope here, but it's a race against time. Some corals host more heat-tolerant strains of zooxanthellae. Corals can also slowly acclimatize over generations. The problem is the pace of change. The ocean is warming faster than many species can adapt. Our job is to slow the change down and protect the corals that show natural resilience.

If the water cools, will the reef come back?

It can, but it's not a simple reset. If the bleaching isn't too severe and conditions return to normal, algae can repopulate the coral. But recovery is slow—years to decades. In the meantime, the reef is less productive, more prone to disease, and may be overgrown by algae. Successive bleaching events, now happening more frequently, don't give reefs time to bounce back, leading to permanent degradation.

Are all bleaching events due to warm water?

No. While warmth is the big one, we've covered the other causes. Cold-water bleaching can even happen during extreme cold snaps! But these are far less common and less devastating on a global scale than thermal bleaching events.

The Bottom Line: Asking what causes coral bleaching leads you to a cascade of interconnected problems. It starts with climate-driven heat, but it's worsened at every turn by local pollution, poor management, and direct human damage. The solution has to be just as multi-pronged. We have to fight climate change with everything we've got, while simultaneously cleaning up our act locally to give every single reef its best fighting chance. The time for action was yesterday, but the next best time is right now.

It's a tough story. There's no sugar-coating it. But understanding the true, layered causes is the first step toward effective action. It moves us past despair and into the realm of targeted, meaningful work. From the choices we make at the ballot box to the sunscreen we buy for a beach day, it all connects back to the health of those vibrant underwater cities we simply cannot afford to lose.

Your comment