Key Insights

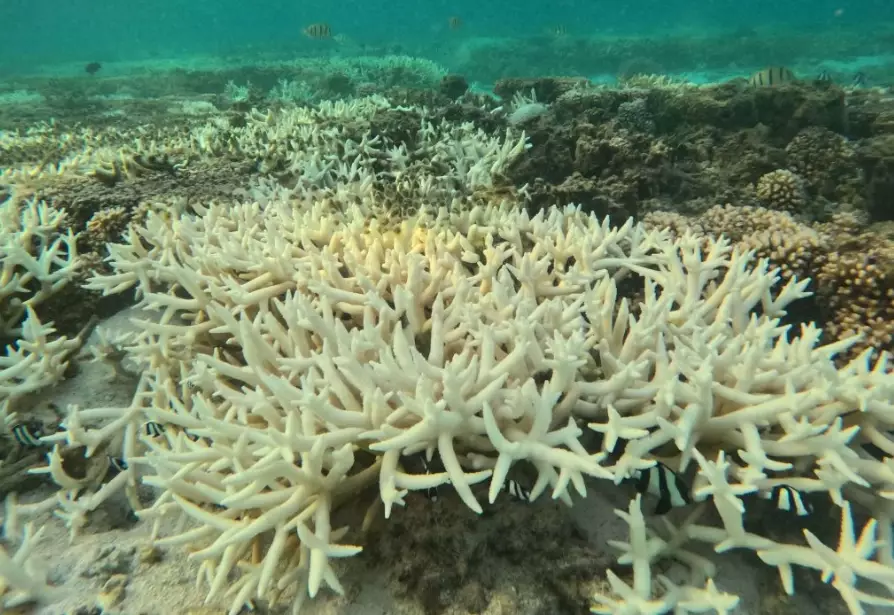

You've probably seen the photos. Stunning underwater landscapes turned into ghost towns, skeletal structures gleaming white under the blue water. Coral bleaching. It looks bad, sure. But if you're asking "why is coral bleaching bad," you might be thinking it's just an aesthetic issue—like a beautiful painting fading. Let me tell you, it's so much worse than that. It's the equivalent of watching a bustling metropolis suddenly have all its grocery stores, hospitals, power plants, and storm walls vanish overnight, leaving the inhabitants to starve, get sick, and be washed away. That's the scale of the disaster we're talking about.

I remember the first time I saw a bleached reef up close. It wasn't on a documentary; it was during a snorkeling trip a few years back. The guide kept pointing to patches of white, his voice flat. "That used to be vibrant purple. That over there was teeming with fish." The silence was the worst part. The reef felt… dead. Not just white, but empty. That experience stuck with me, and it's why I think the question of why coral bleaching is bad needs a deeper answer than most give it. It's not academic. It's visceral.

The Heart of the Matter: It's a Slow-Motion Mass Eviction Notice

First, a quick reality check on what's actually happening. Corals aren't rocks or plants; they're animals. Tiny, soft polyps that live in vast colonies. Their secret superpower is a partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live inside the coral's tissue—think of them as millions of tiny solar panels and food factories rolled into one. The algae photosynthesize, providing up to 90% of the coral's energy (sugars, basically), and in return, they get a safe home and nutrients. It's one of nature's best roommates deals.

Bleaching happens when this relationship breaks down. When the water gets too warm (the main culprit), or too polluted, or too acidic, the coral gets stressed. It's like the coral polyps are saying, "This environment is toxic for my algal buddies." So, they expel them. They kick out their primary food source and their color. What's left is the transparent animal tissue over its white calcium carbonate skeleton. That's the bleached look.

Now, onto the real consequences. When we ask why coral bleaching is bad, we're really asking what happens when these underwater cities fail.

The Domino Effect: From Vibrant City to Barren Wasteland

1. Biodiversity Apocalypse (The Food Web Unravels)

Coral reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, but they support an estimated 25% of all marine life. Let that sink in. One quarter. They are the ultimate biodiversity hotspots. Why is coral bleaching bad for biodiversity? It removes the foundation of the entire ecosystem.

The complex 3D structure of a healthy reef provides everything:

- Nurseries: Countless fish and invertebrate species use the nooks and crannies to hide their young from predators. No structure, no next generation.

- Hunting Grounds: Predators rely on the reef's complexity to ambush prey.

- Specialized Homes: Many species have evolved to live on, or with, specific corals. Lose that coral species to bleaching, and you lose those dependent species forever. It's a direct extinction event.

I've read studies that compare reef fish communities before and after a major bleaching event. The numbers are heartbreaking. The total number of fish can plummet by half or more. The variety of species—the ones that make a reef so fascinating to explore—drops even more sharply. The ecosystem becomes simplified, dominated by generalist species, and much, much poorer.

2. The Human Cost: Livelihoods Washed Away

This is where the abstract "why is coral bleaching bad" becomes painfully concrete for millions of people. Reefs are economic powerhouses.

| Economic Sector | Dependency on Healthy Reefs | Impact of Severe Bleaching |

|---|---|---|

| Fisheries | Reefs are critical breeding and feeding grounds for commercially important fish like snapper, grouper, and lobster. They support subsistence fishing for countless coastal communities. | Catches collapse. Fishermen go further out to sea, at greater cost and risk, for smaller yields. Protein sources vanish, leading to food insecurity. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has extensive data on this vulnerability. |

| Tourism | Diving, snorkeling, and reef-related tourism is a multi-billion dollar global industry. Think Australia's Great Barrier Reef, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia. | Who pays to see a white, dead reef? Tourism revenue dries up. Hotels, dive shops, boat tours, restaurants—entire local economies built around reef beauty face ruin. I've spoken to dive operators who say they now have to carefully choose sites to avoid disappointing tourists, a depressing "bleaching tourism" map. |

| Coastal Protection | Reefs act as natural, self-repairing breakwaters. They dissipate up to 97% of wave energy, buffering coastlines from storms, hurricanes, and erosion. | Dead reefs crumble. Wave energy slams directly into shores. The cost of replacing this protection with artificial seawalls is astronomical. A study by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) highlights how reef loss exponentially increases flood risk. |

| Medicine | Coral reef organisms are treasure troves for biomedical research, with compounds used in treatments for cancer, arthritis, Alzheimer's, and viruses. | We are losing potential cures before we even discover them. It's like burning a library of medical manuscripts we haven't yet learned to read. |

So when someone asks why coral bleaching is bad, ask them to imagine their own job, their town's main industry, and their home's safety all being tied to the health of a single, fragile natural structure. Then imagine watching that structure die.

3. The Cultural Heartbreak

This one gets less press, but it's profound. For many Indigenous and coastal communities, reefs are not just resources; they are woven into cultural identity, traditions, and spirituality. They are part of ancestral history, featured in stories, art, and ceremonies. The loss of a reef is a cultural amputation. It severs a tangible link to heritage and place. That's a different kind of pain, a slow, grieving loss that's hard to quantify but is very real. It's a reason why coral bleaching is bad that transcends economics and ecology.

The Big Picture: A Planet Out of Balance

Zooming out, coral reefs are a planetary vital sign. They are among the first and most sensitive ecosystems to scream in response to climate change. Their mass bleaching is a flashing red alarm on the dashboard of Earth. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports are unequivocal: the primary driver of the increased frequency and severity of mass bleaching events is human-induced global warming.

Why is coral bleaching bad for the planet's systems?

- Carbon Cycling: While reefs aren't massive carbon sinks like mangroves or seagrasses, their destruction releases stored carbon and disrupts local cycles.

- Feedback Loops: Dead reefs don't support the same life. This can alter nutrient cycles and even local weather patterns over time.

- Loss of Resilience: Each major bleaching event weakens the reef system overall. Surviving corals may be more heat-tolerant, but the overall ecosystem is less diverse, less complex, and less able to withstand the next insult, be it a disease outbreak or another heatwave.

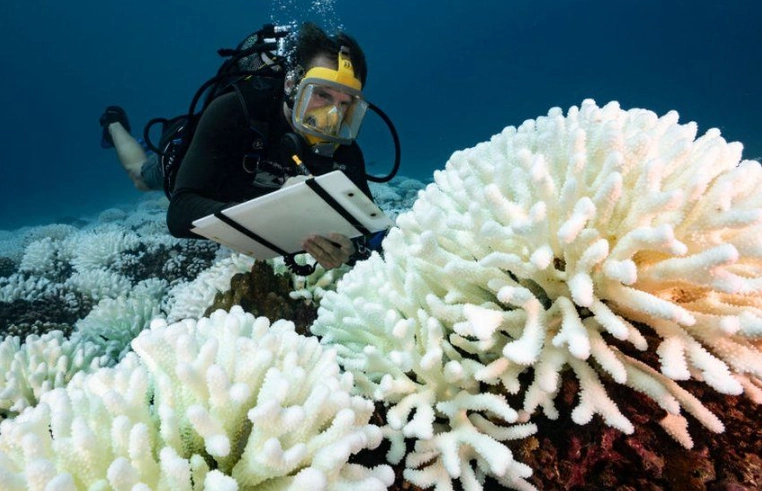

We're pushing these systems past their breaking point. The goal of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force and international bodies isn't just to study the problem, but to fund the urgent restoration and intervention work that might buy reefs some time.

Is There Any Hope? (And What You Can Actually Do)

All this doom and gloom can make you feel helpless. I get it. But understanding why coral bleaching is bad is the first step toward meaningful action. Hope isn't about pretending everything will be fine; it's about focusing on what can still be saved and what we can change.

Scientists are working on amazing, if challenging, fronts:

- Assisted Evolution: Identifying and breeding corals that naturally show higher heat tolerance.

- Restoration: Growing corals in nurseries and outplanting them onto damaged reefs, like underwater reforestation.

- Local Protection: Reducing other stressors like water pollution, overfishing, and physical damage gives reefs a better fighting chance to survive warming periods. The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) works tirelessly on this.

But the single most important thing? Addressing the root cause: climate change. Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions is the non-negotiable, large-scale solution. Everything else is life support.

It's not about guilt. It's about agency.

- Be a Loud Voice: Talk about why coral bleaching is bad. Share articles (like this one), documentaries, and facts. Make it a dinner table conversation. Public pressure drives political action.

- Examine Your Carbon Footprint: Look at your energy use, transportation, and diet. Small, consistent changes add up when millions do them.

- Choose Sustainable Seafood: Use guides from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch to avoid putting pressure on vulnerable reef fisheries.

- If You Visit a Reef: Be a responsible tourist. Use reef-safe sunscreen (mineral-based, no oxybenzone/octinoxate), don't touch or stand on corals, and choose operators with strong environmental practices.

- Support Organizations: Donate to or volunteer with groups doing on-the-ground reef conservation and science, like local marine parks or global NGOs.

Your Questions, Answered

Look, I'm not an alarmist by nature. I prefer solutions to sermons. But after digging into this for so long, the evidence is just too stark to sugarcoat. Understanding why coral bleaching is bad isn't about spreading despair. It's about building a foundation of knowledge that makes inaction impossible. The reefs are telling us something. We need to listen, and more importantly, we need to act.

Your comment