In This Article

- The Heart of the Reef: What Are Zooxanthellae, Really?

- The Break-Up: How Coral Bleaching Actually Happens

- Why Is This Happening? The Stressors Behind the Scenes

- The Bleaching Process: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

- Can They Come Back? The Murky Path to Coral Reef Recovery

- What's Being Done? From Despair to (Guarded) Hope

- Straight Answers to Common Questions

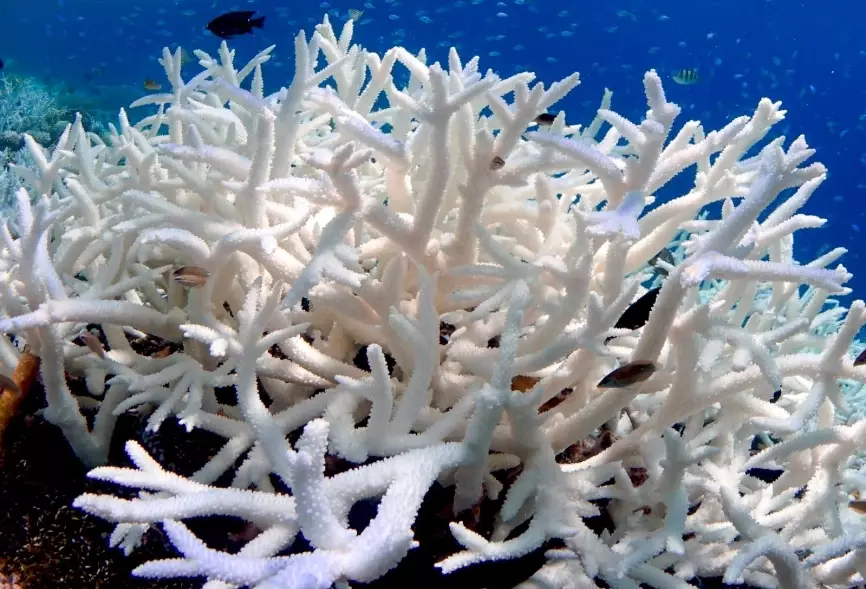

Let's be honest, when most people hear "coral bleaching," they picture a sad, white skeleton on a nature documentary. The narrator's voice gets all serious, and you feel a pang of guilt about your carbon footprint. But what's actually happening inside that coral when it turns white? That's where the story gets fascinating, and frankly, a bit terrifying when you understand it. It all comes down to a microscopic roommate named zooxanthellae.

I remember the first time I saw a bleached coral in person, snorkeling in what was supposed to be a vibrant reef. It was like walking into a forest where all the leaves had fallen off at once. The structure was there, but the life was gone. That eerie white wasn't just a color change; it was a starvation signal. And the culprit and victim of this whole mess is a relationship millions of years old, now falling apart because of us.

The Heart of the Reef: What Are Zooxanthellae, Really?

Forget the complicated genus name Symbiodinium for a second. Think of zooxanthellae (pronounced zoo-zan-thel-ee) as tiny, solar-powered algae that live rent-free inside coral tissue. But it's not a free ride—it's the best deal in the ocean. This partnership is the engine of the entire coral reef ecosystem.

The coral animal, a polyp, provides a safe, sunny apartment inside its clear tissue. It even gives the algae waste products—carbon dioxide and nutrients—which are like fertilizer to a plant. In return, the zooxanthellae, through photosynthesis, crank out sugars, glycerol, and amino acids. We're talking about up to 90% of the coral's daily nutritional needs coming from this internal farm. The coral uses this energy to grow, build its limestone skeleton, and reproduce. Without the zooxanthellae, most reef-building corals in clear, tropical waters would struggle to survive. They'd be stuck in slow motion.

The bottom line? Coral isn't a plant. It's an animal that outsources its cafeteria to millions of microscopic algae. The famous brilliant colors of a healthy reef—the neon greens, vibrant purples, deep browns—aren't usually the coral's own color. They're mostly the pigments of the zooxanthellae living inside them. When you see a colorful reef, you're basically looking at the world's most beautiful algal bloom, perfectly packaged.

The Break-Up: How Coral Bleaching Actually Happens

So, bleaching. It sounds passive, like the color is washing out. It's not. It's a violent divorce.

When corals get stressed—and the number one stressor is elevated water temperature—the harmonious relationship with their zooxanthellae goes sour. Think of the coral polyp getting a fever. The exact biochemical trigger is complex, but the heat disrupts the photosynthetic machinery inside the algae. They start producing toxic levels of reactive oxygen species—basically, biological pollution.

The coral polyp, feeling sick and poisoned by its own partners, has a drastic survival response: it expels them. It forcibly evicts millions of its zooxanthellae from its tissue. Or, in some cases, the algae pack up and leave on their own. The result is a transparent coral polyp sitting on a white limestone skeleton. You see the bone-white calcium carbonate through the clear tissue. That's the "bleached" look.

Crucially, the coral is still alive at this point.

But it's a patient on life support, starving. Its main food source is gone. It can still catch some plankton with its tiny tentacles at night, but it's like trying to feed a marathon runner with a single pea. If cool conditions return quickly, the coral can sometimes recruit new zooxanthellae from the water and slowly recover. But if the stress persists—weeks, months—the coral will literally starve to death. The tissue dies, leaving nothing but the barren, white skeleton, which quickly gets covered in slimy algae.

Biggest misconception: Bleached coral is not dead coral. It's severely stressed and starving coral. The window for recovery is open, but it's slamming shut faster than ever.

Why Is This Happening? The Stressors Behind the Scenes

Everyone points at warming seas, and for good reason. Mass bleaching events on a global scale are directly linked to climate change and marine heatwaves. But the story of zooxanthellae and coral bleaching isn't a one-villain plot. It's a tag team of stressors that weaken the coral until the heat delivers the final blow.

The Primary Driver: Temperature Stress

Corals live near their upper thermal tolerance limit. Just a sustained increase of 1-2°C above the usual summer maximum can trigger bleaching. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) maintains a satellite-based coral bleaching alert system that tracks these anomalies globally, and the maps are getting alarmingly red more frequently. The heat doesn't just come from the air; it's compounded by calm, sunny conditions that allow the water to heat up even more.

The Supporting Cast of Stressors

- Solar Irradiance: Intense sunlight, especially UV radiation, acts in concert with high temperature to damage the zooxanthellae's photosynthetic systems. It's a double whammy.

- Pollution & Runoff: This is a huge local factor. Fertilizer runoff, sewage, and sedimentation from coastal development pollute the water. Excess nutrients favor growth of macroalgae that smother corals, and the murky water blocks light, stressing the light-dependent zooxanthellae. Sediment can also physically smother the polyps.

- Ocean Acidification: The other CO2 problem. As the ocean absorbs more carbon dioxide, it becomes more acidic. This makes it harder for corals to build their skeletons. A weakened, energy-depleted coral is less resilient to other stresses, including heat. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports consistently highlight the combined threat of warming and acidification.

- Disease: Stressed corals are more susceptible to disease, which can spread rapidly through a bleached population, finishing them off.

It's this combination—the global pressure of climate change plus local pressures of poor water quality—that's pushing reefs over the edge. A reef already struggling with pollution has a much lower threshold for surviving a heatwave.

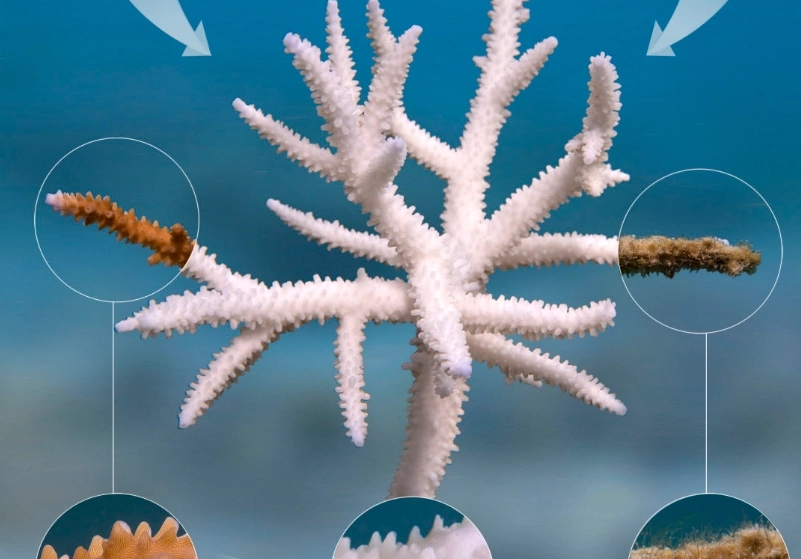

The Bleaching Process: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Let's walk through the stages of what happens from stress to potential death. It's not an instant switch.

| Stage | What's Happening in the Coral | Visible Signs | Coral's Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Stress | Healthy symbiosis. Zooxanthellae are photosynthesizing efficiently, providing >90% of coral's energy. | Full, rich coloration. Polyps may be extended. | Thriving, growing. |

| Onset of Stress | Water temperature rises 1-2°C above normal. Photosystem in zooxanthellae becomes damaged, producing toxins. | Corals may appear unusually bright or "fluorescent." This is a protective stress pigment response. | Stressed but functioning. |

| Active Bleaching | Coral expels zooxanthellae in large numbers. Pigment concentration plummets. | Patchy or full loss of color, revealing white skeleton. Tissue is still transparent. | Starving. Alive but in crisis. |

| Prolonged Bleaching | No zooxanthellae, no energy production. Coral metabolizes its own reserves and tissues. | Bone-white, possibly with a fuzzy algal film starting. Tissue may look shrunken. | Severely compromised. Mortality risk is high. |

| Recovery or Death | If temps drop: may slowly re-acquire zooxanthellae. If stress continues: tissue necrosis. | Recovery: pale color slowly returns. Death: bare skeleton, overgrown by algae. | Either convalescing or dead. |

See, the process of zooxanthellae and coral bleaching isn't a single event. It's a cascade failure. And the time between Stage 2 and Stage 5 is getting shorter.

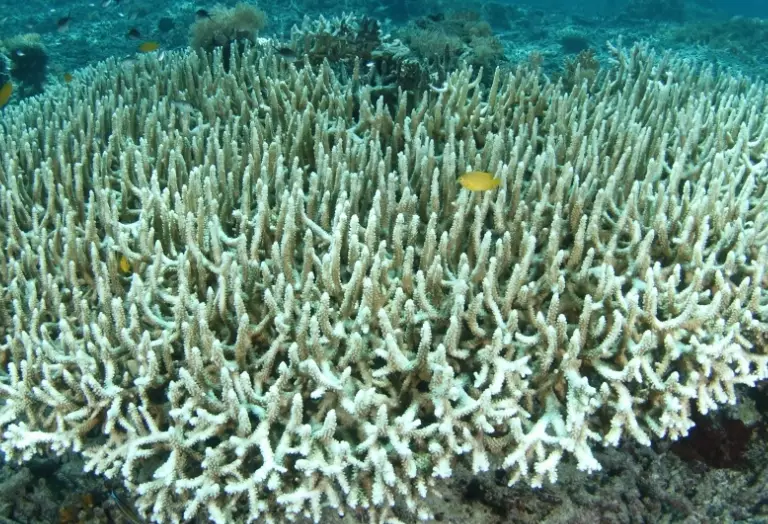

Can They Come Back? The Murky Path to Coral Reef Recovery

This is the million-dollar question. The answer is a frustrating "it depends." Recovery isn't just about the zooxanthellae moving back in. It's about the entire reef system.

For an individual coral colony, recovery is possible if the stress is brief. It can take in new, possibly more heat-tolerant strains of zooxanthellae from the water. But this is an energy-intensive process for an already weakened animal. Growth and reproduction are put on hold for years. I've seen colonies that survived a 2016 bleaching event that still look skinny and pale compared to their unbleached neighbors.

On an ecosystem scale, recovery is a much taller order. It requires:

- Source of New Coral Larvae: Healthy, mature corals nearby that can spawn and supply larvae to repopulate the dead areas.

- Good Water Quality: Clear, clean water for the larvae to settle and for the new recruits to thrive without local stressors.

- Time and Stability: Decades of no major bleaching events, storms, or disease outbreaks to allow slow-growing corals to mature.

The problem is, with bleaching events now hitting some reefs like clockwork every few years (the Great Barrier Reef had major events in 2016, 2017, 2020, and 2022), that "time and stability" part is vanishing. The reef doesn't get a chance to heal before the next wound opens.

What's Being Done? From Despair to (Guarded) Hope

It's easy to feel hopeless. But scientists, conservationists, and local communities are scrambling for solutions. The strategy is two-pronged: tackle the global root cause and buy time with local action.

The Global Fix: Slashing Emissions

This is non-negotiable. Every fraction of a degree of warming we prevent matters. Stabilizing the climate is the only long-term solution to stop the relentless drive of mass bleaching events. All other actions are essentially triage.

The Local Triage & Assisted Evolution

This is where it gets interesting. People are trying to help corals adapt on human, not geological, timescales.

- Coral Gardening & Restoration: Growing hardy coral fragments in nurseries and outplanting them onto degraded reefs. Organizations like the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) support and coordinate many of these efforts globally.

- Selecting for "Super Corals": Identifying individual corals that naturally survived a bleaching event, assuming they have some resilience (maybe from tougher zooxanthellae strains), and using them as broodstock for restoration.

- Algal Manipulation: Research is looking at intentionally injecting corals with strains of zooxanthellae known to be more heat-tolerant. It's like giving the coral a better air conditioner for its internal factory.

- Managing Local Stressors: This is critical. Creating marine protected areas, improving wastewater treatment, and managing coastal development to reduce runoff gives reefs their best possible chance to withstand the global heat stress they can't escape.

Let me be cynical for a second: some of this feels like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic if emissions keep rising. But the local work is vital. It protects the genetic diversity—the potential survivors—and maintains pockets of resilience that might one day be the seed for recovery in a cooler future.

Straight Answers to Common Questions

You've probably got more questions. Here are the ones I hear most often, answered plainly.

Does bleaching kill the zooxanthellae too?

Not necessarily. When expelled, many zooxanthellae are still alive and can persist in the water column, waiting for another host. The coral is the one that usually gets the worse end of the deal.

Can a bleached coral recover its color?

Yes, if it recovers. But the color might be different. New zooxanthellae strains can impart different pigments. A recovered coral might be a paler shade of its former self.

Are all corals equally susceptible to bleaching?

No. Some species are tough as nails; others are super sensitive. Fast-growing branching corals (like staghorn) often bleach first and die fastest. Massive, slow-growing corals (like brain corals) tend to be more resistant but recover more slowly. The loss of the fast-growers dramatically changes the reef's structure and function.

What can I, as an individual, actually do?

First, reduce your carbon footprint. Vote for climate action. Second, if you visit a reef, be a responsible tourist: don't touch corals, use reef-safe sunscreen, choose eco-conscious operators. Third, support organizations doing credible reef conservation and science. Finally, talk about it. The link between zooxanthellae and coral bleaching isn't just marine biology; it's a stark indicator of a planet under stress.

Is there any good news?

Corals have been around for hundreds of millions of years. They've faced changes before. They are resilient. The question is whether our actions will outpace their ability to adapt. The good news is that we understand the problem completely. We know exactly why zooxanthellae and coral bleaching is happening. And knowing the problem is the first, essential step to fixing it. The solutions—both cutting emissions and local protection—are also clear. We just need the will to do it at the scale required.

Look, it's a dire situation.

But understanding the intimate, fragile dance between a coral polyp and its microscopic algae is where the wonder and the warning both lie. This isn't a remote environmental issue. It's the breakdown of a fundamental biological partnership, one that supports ecosystems, fisheries, and coastlines for millions of people. When we talk about saving the reefs, we're really talking about preserving the conditions that allow this ancient, miraculous symbiosis between zooxanthellae and coral to continue. Everything else—the beauty, the biodiversity, the coastal protection—flows from that.

Your comment