Quick Dive Guide

- The First Type: The Compact Dive (Your Foundation)

- The Second Type: The Track Start (The Powerhouse)

- The Third Type: The Grab Start (The Aerodynamic Missile)

- Side-by-Side: Choosing Your Dive

- Drills and Dryland Work to Improve Any Dive

- Safety First: The Non-Negotiables

- Answering Your Burning Questions

- Wrapping It Up: Your Action Plan

Let's be honest. For a lot of people, the dive is the most intimidating part of swimming. You stand there on the edge, the water looks miles away, and your brain starts listing all the ways it could go wrong. I remember my first attempts—more of a frantic, flailing flop than a dive. A huge splash, stinging skin, and zero forward momentum. It was frustrating.

But here's the thing I learned much later: a good dive isn't about bravery; it's about technique. And contrary to what you might think, there isn't just one "right" way to do it. In fact, mastering the different entries can completely change your relationship with the water, whether you're doing laps for fitness or racing the clock.

So, let's cut through the confusion. When we talk about the 3 types of diving in swimming, we're usually referring to the core techniques used from a poolside starting position. We're not talking about scuba or cliff diving here. This is about getting from the deck into the water as efficiently as possible. The three main ones are the Compact Dive (or Standing Dive), the Track Start, and the Grab Start. Each has its place, its purpose, and its own little quirks.

Why does this even matter? Well, a sloppy dive can ruin your rhythm before you've even taken a stroke. It wastes energy and, for competitive swimmers, can cost precious tenths of a second. For beginners, a bad experience can reinforce a fear of the water. But a clean, controlled entry sets you up for a powerful, streamlined swim. It feels incredible when you get it right.

The First Type: The Compact Dive (Your Foundation)

This is where everyone should start. The compact dive, often called the standing dive or beginner's dive, is the cornerstone. It's the safest, most controlled of the three types of diving in swimming, and it teaches you the fundamental body positions you'll need for the more advanced ones.

The goal here isn't maximum distance or speed—it's control and a clean, splash-free entry. You learn to become an arrow, not a cannonball.

Breaking Down the Mechanics

It looks simple, but every part of your body has a job to do.

You start standing upright at the pool's edge, toes curled over (if possible). Your arms are straight up, ears tucked between your biceps. This is the "streamline" position, and it's the shape you want to hold through the air and into the water. From here, you bend your knees, lean forward, and let gravity start to pull you. Don't jump up; think about pushing your hips forward and up, following your fingertips. Your body should follow a smooth, arcing path.

The entry is key. You want to hit the water with your hands first, head tucked down, followed by your arms, shoulders, torso, hips, and legs—all going through the same "hole" in the water. It should be a clean "shoosh" sound, not a loud "smack."

Where Beginners Go Wrong (And How to Fix It)

We've all seen it—the belly flop. It's usually caused by fear, which makes the diver hesitate and land flat. Other common mistakes:

- Looking up: Your head follows your eyes. If you look at the far wall, your chest will come up and your legs will drop. Keep your chin tucked to your chest.

- Jumping out, not down: This creates a huge, braking arc. You want a tighter, steeper curve.

- Legs apart, toes not pointed: This creates drag instantly. Squeeze everything from your glutes to your calves.

My biggest piece of advice? Practice the motion on land first. Get used to the feeling of leaning forward into the streamline. Then, start in the water. Stand in the shallow end, bend over, and push off the bottom in a streamline. Feel what it's like to glide. It builds confidence.

The Second Type: The Track Start (The Powerhouse)

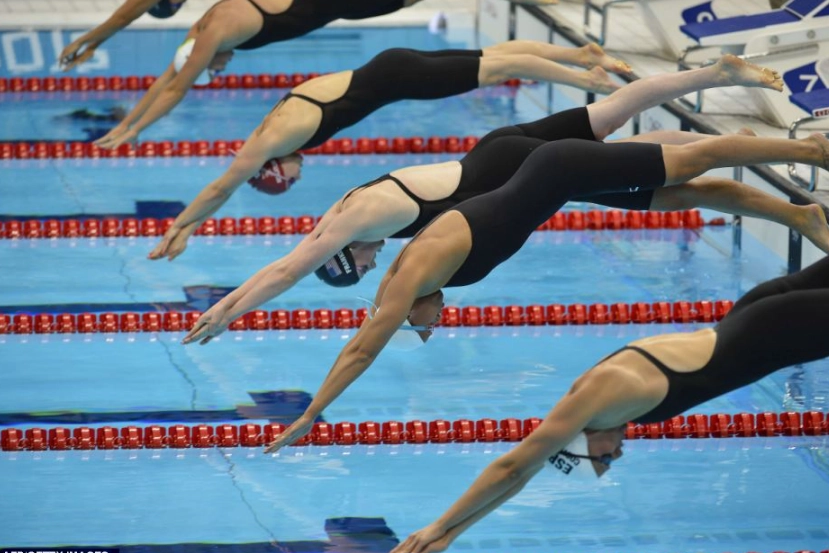

Now we're getting into the realm of competitive swimming. The track start is one of the two main racing starts and is arguably the most popular worldwide. It's called a "track start" because the stance resembles a sprinter in the blocks: one foot forward, one foot back.

This style offers a great balance of explosive power and stability. Because you have a wider base of support, you feel more secure on the block, which can be a huge mental boost. The power comes from driving off both legs simultaneously, but with the rear leg providing a massive initial push.

The Stance and Launch Sequence

Your front foot is at the front edge of the block, toes gripping. Your back foot is placed further back, usually with just the ball of the foot on the block for a longer push-off. Your body weight is forward, most of it over that front leg. Your hands can be on the front edge of the block or, more commonly, you grab the block between your feet.

At the start signal, you pull your body forward with your hands (if grabbing) and drive forward with your hips. The back leg fires first, followed immediately by a powerful extension from the front leg. You swing your arms forward into a streamline as your body lifts. The motion is forward and out, aiming for a longer, flatter trajectory than the compact dive.

Who Should Use the Track Start?

This is the workhorse for most competitive swimmers from high school up to the Olympic level. It's particularly favored in shorter sprints (50m, 100m) where reaction time and raw explosion are critical. Swimmers with stronger leg drive often excel with it.

But it's not just for elites. Intermediate lap swimmers who want a more powerful push-off can adapt a simplified version. The stability of the stance makes it less daunting than the next option for many.

The Third Type: The Grab Start (The Aerodynamic Missile)

The grab start is the other primary racing start, and it's all about minimizing time on the block and maximizing aerodynamic flight. In this start, both feet are at the front of the block, side-by-side or nearly so. You bend down and literally grab the front edge of the starting block.

This position is inherently less stable than the track start—you're essentially on your toes—but it allows for a faster reaction time because your center of gravity is already far forward. The launch is incredibly quick.

Executing the Grab

Toes at the edge, feet hip-width apart. Bend your knees deeply and lean forward until you can comfortably grab the block. Your back should be rounded, head down. On the signal, you don't "push" off in the traditional sense. Instead, you let go of the block and allow your already-forward-leaning body to fall, while simultaneously snapping your legs straight to catapult yourself forward.

The flight path is typically quicker and steeper than the track start. You enter the water at a sharper angle, which can lead to a faster underwater phase if done correctly. However, the margin for error is smaller. Lean too far and you might false start or dive too deep. Not enough, and you'll have a weak launch.

The Ongoing Debate: Track vs. Grab

Which is better? It's a hot topic. Studies and expert opinions swing back and forth. Some research, like analysis promoted by SwimSwam, a leading swimming news site, has suggested the grab start might have a slight reaction time advantage. However, the difference is often milliseconds and heavily depends on the individual swimmer's physiology, strength, and technique.

Many coaches believe the track start provides more consistent power, especially over multiple races in a meet. The best advice is to try both extensively under a coach's eye. Your body will often tell you which one feels more natural and powerful.

Side-by-Side: Choosing Your Dive

So, you've got these 3 types of diving in swimming laid out. How do you pick? It's not one-size-fits-all. Your choice should depend on your goals, experience, and even the specific race or situation.

| Dive Type | Best For | Key Advantage | Biggest Challenge | Body Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compact Dive | Absolute beginners, recreational swimmers, teaching body alignment. | Safety, control, foundational skill building. | Overcoming the fear of leaning forward and going in head-first. | Core tension, full-body streamline. |

| Track Start | Most competitive swimmers, intermediate fitness swimmers, those wanting more power. | Stability on the block, powerful two-leg drive, consistent performance. | Coordinating the rear and front leg drive for a unified explosion. | Leg power (quads, glutes), hip drive. |

| Grab Start | Advanced competitive swimmers, sprinters, those with excellent reaction time. | Potentially faster reaction off the blocks, aerodynamic entry. | Maintaining balance in a precarious starting position; shoulder strain. | Explosive leg extension, shoulder/back strength for the pull. |

Look, if you're just starting out, don't even glance at the grab start. Master the compact dive until it's second nature. The confidence and body awareness you gain are priceless. I made the mistake of trying to copy the Olympic grab start before I could do a clean standing dive, and it set me back months.

For the fitness swimmer who knows the basics, dabbling in a basic track start stance can add some fun and power to your lap sessions. Just take it slow.

Drills and Dryland Work to Improve Any Dive

You don't always need a pool to work on your dive. A lot of the issues stem from weak links in the kinetic chain or poor neuromuscular coordination.

Dryland Drills for Power & Posture

- Wall Streamline Holds: Stand with your back against a wall. Press your head, upper back, hips, and heels against it. Raise your arms into a tight streamline, trying to press your biceps against your ears and the back of your hands against the wall. Hold for 30 seconds. This teaches the full-body tension you need.

- Squat Jumps into Streamline: From a squat position, explode upward. At the peak of your jump, snap into a tight streamline. Land softly. This links leg power to the core and arm position.

- Medicine Ball Throws: (For track/grab starts). Holding a med ball, get into your starting stance. Explosively throw the ball forward as you simulate your launch. This trains the horizontal power transfer.

In-Water Correction Drills

- Kneeling Dive: Start from one knee at the pool's edge. This limits your power, forcing you to focus on the lean and clean entry. Great for combating the "jump up" instinct.

- Dive to Glide, No Stroke: Dive in and hold your streamline as long as possible. Count how far you glide. The goal is distance, not immediate stroking. This highlights the value of a good entry.

- Partner Feedback: Have someone watch from the side. They can tell you if your legs are apart, if you're looking up, or if your entry is flat. Video is even better—it's brutally honest.

Consistency beats intensity here. Five minutes of focused dive practice at the start of every swim session will yield better results than one frantic hour of trying to fix everything at once.

Safety First: The Non-Negotiables

Before you try any of this, we have to talk safety. Diving into shallow water is a leading cause of serious spinal injuries. The rules are simple but absolute.

Never, ever dive into water where you cannot see the bottom or do not know the depth. This includes lakes, rivers, and the ocean. Even in a pool, the American Red Cross and other safety bodies emphasize that recreational diving should only be done in water at least 9 feet deep, and even then, head-first entries should be straight forward, not at an angle. Competitive racing starts are performed under controlled conditions in deep water.

For learning, always have a competent observer or lifeguard present. If you feel even a hint of pain in your neck or back during a dive, stop immediately and seek assessment. It's not worth the risk.

Honestly, this safety talk is more important than any technique tip. I've seen too many people get cocky at a pool party.

Answering Your Burning Questions

“I'm terrified of going in head-first. How do I start?”

Start in the shallow end. Literally. Practice falling forward from a crouch, leading with your hands, and just letting your body follow. Do it where you can stand up immediately. The goal is to desensitize yourself to the feeling. Then practice pushing off the bottom in a streamline. The dive is just a more committed version of that push. Go at your own pace.

“Why do my legs always slap the water?”

This almost always means your upper body is rising before entry, causing your legs to drop. You're likely looking up or trying to "jump" rather than "dive." Focus on keeping your chin tucked and driving your hips upward during the launch. Think of your body as a seesaw—if your head goes up, your feet go down.

“Which of the 3 types of diving in swimming is the fastest for racing?”

There's no universal answer. At the elite level, the choice between track and grab is highly personal. Some swimmers are faster with one, some with the other. The difference is often smaller than the difference made by perfecting your underwater dolphin kicks off the start. The best start is the one you can execute with perfect technique, consistently, under pressure. For most, that tends to be the track start due to its stability.

“How deep should I go after my dive?”

For a compact dive, not very deep—just enough to get fully submerged in a streamline. For racing starts, you want to enter at an angle that allows you to glide to about 3-5 feet under the surface before starting your underwater kicks. The official rules from the International Swimming Federation (FINA) state you must surface by 15 meters. The ideal is a smooth, hydrodynamic glide just below the surface turbulence.

“My dive feels weak. Is it my technique or am I just not strong enough?”

It's almost always technique, especially at the beginner and intermediate levels. Strength helps, but proper sequencing of the movement—lean, drive, streamline—creates far more power than raw muscle. A weak dive is usually a dive where the power is going in the wrong direction (up instead of out) or is being lost because the body is loose and not arrow-straight. Film yourself. You'll likely see the leak.

Wrapping It Up: Your Action Plan

Understanding the 3 types of diving in swimming is the first step. The next is honest self-assessment. Where are you now?

If you're new, commit to the compact dive. Drill it. Make it automatic. The comfort you gain will open doors to everything else.

If you're a competitive swimmer or a serious fitness swimmer stuck in a rut, pick one racing start—probably the track start—and deconstruct it. Work on the dryland components. Film yourself from the side. Get feedback. Be patient; changing a motor pattern takes hundreds of repetitions.

The dive is a skill, separate from swimming. It deserves its own dedicated practice time. Don't just do it as a rushed way to start your workout. Give it focus, and the payoff in confidence, speed, and sheer enjoyment of the sport will be immense.

Now go get wet. And try to make a smaller splash.

Your comment