Quick Navigation

Let's be honest. When you watch a diver fly through the air with what seems like effortless grace, you're probably not thinking about the springboard diving equipment beneath their feet. But you should. That board is the launchpad for everything. It's the difference between a splash and a swan, between a practice session and a personal best. I remember the first time I stepped onto a properly calibrated board versus the old, worn-out one at my local pool. The feeling was night and day. One felt like a trampoline made of concrete, the other like a trusted partner. That's what we're talking about here.

This isn't just a shopping list. It's a deep dive (pun intended) into the world of springboard diving gear. Whether you're a parent outfitting a budding club diver, a facility manager responsible for safety, or a seasoned athlete fine-tuning your setup, getting this right matters. We'll strip away the marketing jargon and look at what really makes a difference in performance, safety, and longevity. Forget the fluff. Let's talk about metal, fiberglass, fulcrums, and how not to waste your money.

Breaking Down the Basics: What Actually Constitutes Springboard Diving Equipment?

Most people just see "the board." But it's a system. A complete setup involves several key components working in harmony. Miss one, and the whole thing is off.

The Board Itself: More Than Just a Plank

This is the star of the show. Modern diving boards are marvels of engineering, designed to store and release energy. They're not simple planks of wood anymore (thankfully). The core is usually an aluminum I-beam or a box beam, surrounded by a fiberglass composite shell. The length, width, and thickness are all tuned for specific performance characteristics.

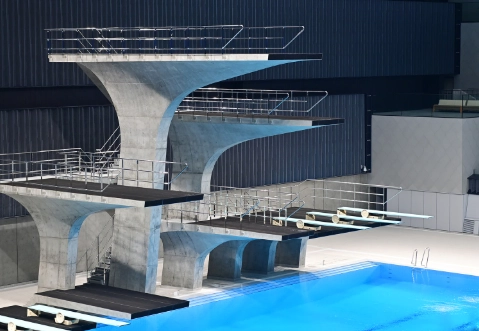

You've got two main types in competitive and serious recreational use: the fulcrum-based springboard (the standard 1m and 3m boards you see everywhere) and the much rarer, much stiffer platforms (5m, 7.5m, 10m). Since we're focusing on springboards, let's stick with the fulcrum type. The magic is in the flex. A board that's too stiff won't give you the lift; one that's too whippy can be uncontrollable. It's a Goldilocks situation.

Materials matter immensely. Cheap boards might use lower-grade fiberglass or have a weak core. They'll lose their pop, develop a dead spot, or worse, crack. I've come across boards where the surface texture was worn smooth, becoming a slip hazard in wet conditions. Not good.

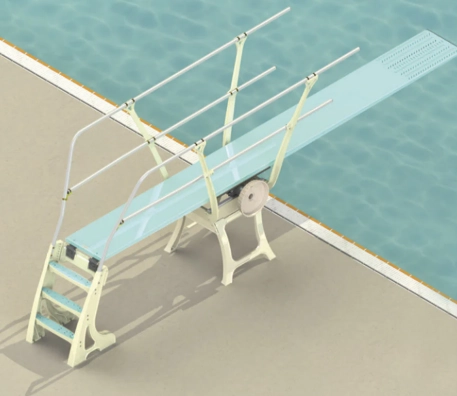

The Fulcrum: The Secret Control Knob

If the board is the engine, the fulcrum is the throttle. This movable roller mechanism sits underneath the board. By sliding it forward or backward, you change the board's effective length and, therefore, its stiffness and spring.

Move it toward the pool (forward), and the diving end of the board becomes longer and more flexible—more bounce. Move it back toward the diver, and the board acts shorter and stiffer—less bounce, faster reaction. Divers adjust this constantly based on their weight, the dive they're attempting, and even how they're feeling that day. A good fulcrum moves smoothly, locks securely, and has clear, numbered markings for repeatable settings. A bad one is stiff, grinds, and can slip. I once saw a fulcrum with a broken locking pin held together with duct tape. Please don't let that be you.

The Stand and Base: The Unsung Heroes

All that force from the jump has to go somewhere. The stand—the metal structure holding the board—and its base, which anchors it to the deck, absorb incredible amounts of stress. This isn't the place to cut corners. A wobbly stand isn't just annoying; it's dangerous. It introduces unpredictability and can fail catastrophically.

High-quality stands are made from heavy-gauge, corrosion-resistant stainless steel or hot-dipped galvanized steel. The base should be massively over-engineered, bolted into a concrete foundation, not just sitting on the pool deck. The hinge mechanism where the board attaches to the stand needs to be robust and allow for a full, smooth range of motion. Anything that creaks, groans, or has visible rust in critical areas is a red flag.

The Mat or Non-Slip Surface

Ever tried to run and jump on a wet, smooth surface? It's a disaster waiting to happen. The top surface of the board is covered with a specialized non-slip material, often called a diving mat or tread. It's usually a rough, sandpaper-like epoxy coating or a sheet of abrasive material.

This might seem trivial, but it's critical for safety. It provides the traction needed for a powerful, controlled hurdle and take-off. When this surface wears down (and it will), it becomes slick. Replacing or resurfacing it is not an optional maintenance task. Some facilities try to paint over it with regular paint, which is a terrible idea—it creates an incredibly dangerous, slippery surface when wet.

A Practical Buyer's Guide: What to Look For (And What to Avoid)

So you need to buy some springboard diving equipment. Maybe for a school, a club, or a backyard pool (if you're going all out). The market can be confusing. Here’s a no-nonsense breakdown.

First, know your codes. In the United States, diving equipment should comply with standards from the NSF International (specifically NSF/ANSI 50 for pool equipment) and, for competitive settings, the regulations set by FINA (Fédération Internationale de Natation), the world governing body for aquatic sports. Compliance isn't just a sticker; it's a benchmark for material quality, structural integrity, and safety testing.

Here’s a comparison to help you visualize the key decision points:

| Feature | Budget/Residential Grade | Commercial/Club Grade | FINA-Competition Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Material | Standard aluminum I-beam, thinner gauge. | Heavy-duty aluminum or steel box beam. | Precision-engineered aluminum box beam, specific flex profile. |

| Surface Tread | Applied epoxy coating, less durable. | High-abrasion, replaceable tread sheet. | FINA-approved non-slip surface, often a specific type of grit. |

| Fulcrum Mechanism | Basic roller, manual lock, fewer settings. | Smooth-rolling roller with positive lock, numbered scale. | Precision-machined roller with micro-adjustments, flawless action. |

| Stand Construction | Lighter steel, standard galvanization. | Heavy-gauge, corrosion-resistant stainless or galvanized steel. | Ultra-robust stainless steel, engineered for zero deflection. |

| Warranty | Limited, often 1-5 years. | Extended, 10+ years on structure. | Varies, but built for decades of heavy use. |

| Best For | Low-traffic home pools, basic fun. | Public pools, high schools, diving clubs, daily training. | National/International competitions, elite training centers. |

My advice? Unless it's for very occasional, supervised use at home, lean towards commercial-grade equipment. The price jump from budget to commercial is significant, but the jump from commercial to FINA is astronomical and usually unnecessary for non-elite training. The commercial grade offers the best balance of durability, safety, and performance for the money. I've seen residential-grade boards in semi-public settings get destroyed in a single season.

The Installation Factor: It's Not a DIY Project

This is a huge point that many facilities overlook. You can buy the best springboard diving gear in the world, but if it's installed poorly, it will perform poorly and may be unsafe. Installation is not for your general handyman.

It requires understanding load dynamics, concrete anchoring, precise leveling, and alignment. The base must be secured to a properly engineered concrete footing, often specified by the manufacturer. The board must be perfectly level from side to side. The fulcrum must travel freely. Hire a professional installer who specializes in aquatic equipment. It's worth every penny. A bad install can void warranties and create liability nightmares.

Maintenance: Keeping Your Springboard Diving Equipment in Top Shape

Buying it is one thing. Keeping it safe and functional is another. Neglect is the biggest killer of diving equipment.

Let's run through a simple maintenance checklist. This should be done monthly for a busy facility, quarterly for lighter use.

- Visual Inspection: Look for cracks, chips, or delamination in the fiberglass shell, especially around the fulcrum area and the tip. Check for any rust or corrosion on the stand, hinges, and bolts.

- Surface Check: Run your hand over the non-slip tread. Does it still have a consistent, gritty texture? Are there smooth, worn patches? If water doesn't bead up and instead sheets across a large area, the surface may be compromised.

- Fulcrum Test: Move the fulcrum through its entire range. Does it move smoothly without binding? Does the locking mechanism engage firmly and hold the roller in place without slipping?

- Stability Check: Push down on the end of the board and release. It should rebound smoothly without any odd noises (creaks, grinding, clunks). Check for any lateral (side-to-side) wobble in the board or stand.

- Fastener Tightness: Check all visible nuts and bolts on the stand and base for tightness. Don't over-torque, but ensure they are snug.

Cleaning is simple but important. Rinse the board with fresh water regularly to remove chlorine and salt buildup, which can degrade materials over time. Use a mild detergent for grime, but avoid harsh chemicals, abrasive pads, or pressure washers directed at seals and bearings.

One common issue is a "dead spot"—a place on the board that seems to have lost its spring. This can be caused by internal damage to the core or a problem with the fulcrum/stand alignment. It's often a job for a professional technician.

Answering Your Burning Questions (FAQ)

I get asked a lot of questions about this stuff. Here are the most common ones, answered straight.

Wrapping It Up: Making an Informed Choice

Choosing the right springboard diving equipment boils down to understanding your needs, respecting the engineering, and committing to maintenance. It's an investment in safety and performance.

Don't get dazzled by fancy terms. Focus on the fundamentals: a solid core, a robust stand, a smooth fulcrum, and a grippy surface. Buy for the use case you actually have, not the one you dream of. And for heaven's sake, get it installed by a pro.

Good equipment, properly cared for, becomes a reliable partner. It gives divers the confidence to push their limits, knowing the platform beneath them is secure. And that, in the end, is what it's all about—creating an environment where skill, not faulty gear, is the only limit.

Your comment