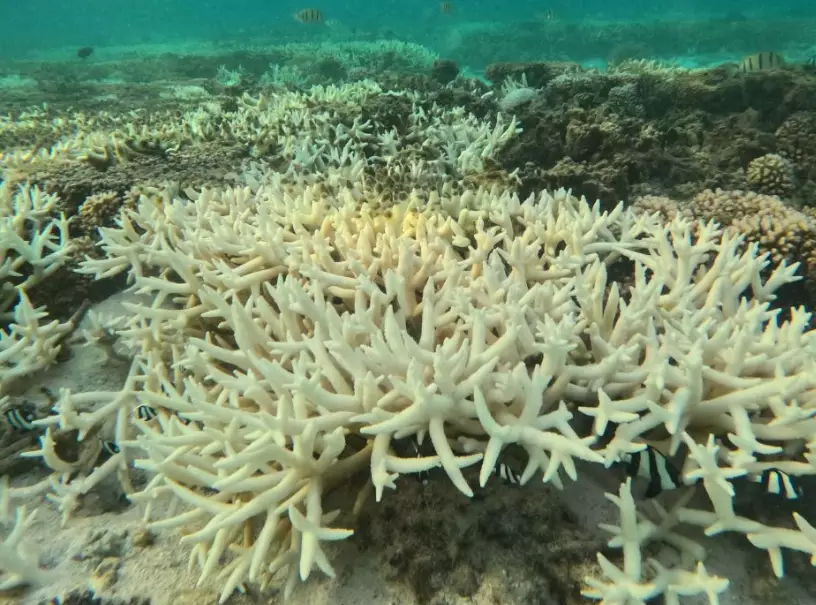

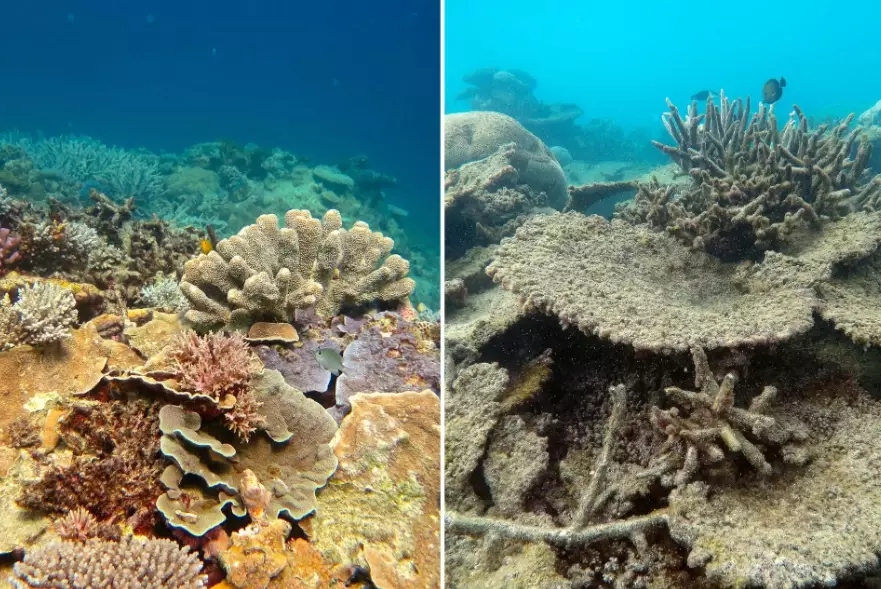

You see the photos. A once-vibrant coral garden, now a ghostly white graveyard. Coral bleaching has become a familiar headline, a symbol of a warming ocean. But here's what most articles miss: the bleaching event itself is just the opening scene. The real story, the one with lasting consequences for everything from your favorite dive site to the fish on your plate, is what happens next. The environmental impact of coral bleaching is a slow-motion domino effect that reshapes entire seascapes. I've watched it happen over two decades of diving—the silence that follows the color is what stays with you.

What You’ll Discover

How Coral Bleaching Unfolds: The Science Simplified

Let's clear up a major misconception. Bleaching isn't death. Not immediately. It's a severe stress response. Corals are animalsthat host microscopic algae called zooxanthellae in their tissues. It's a perfect partnership: the algae get a safe home and CO2, and in return, they provide up to 90% of the coral's food through photosynthesis.

When seawater temperatures rise just 1-2°C above the usual summer maximum for a few weeks, this partnership breaks down. The stressed coral expels its colorful algal tenants. Since the algae provide the color, the coral's transparent tissue reveals its white limestone skeleton underneath. Hence, "bleached."

The Critical Window: A bleached coral is starving, but it's still alive. If water temperatures drop quickly—within a few weeks—the algae can return, and the coral may recover. But if the heat stress persists, or if other stressors like pollution are present, the coral will die from disease or outright starvation. This is the fragile tipping point that determines the fate of an entire ecosystem.

The Domino Effect: Environmental Impacts of Bleached Reefs

This is where the chain reaction begins. A single bleached coral colony is a tragedy. A fully bleached reef triggers an ecosystem collapse. The impacts cascade through every level.

1. Biodiversity Implosion

Coral reefs are the rainforests of the sea, housing about 25% of all marine species. They don't just live on the reef; they depend on it. When corals die, the complex 3D structure they built begins to erode. Fish that relied on nooks for shelter—like many juvenile species—disappear. Invertebrates that fed on coral mucus or tissue have to move or starve. I've seen reefs where the list of missing species reads like a who's who of tropical diving: butterflyfish, parrotfish (crucial algae grazers), cleaner shrimp. The silence is auditory too; the pops and cracks of a healthy reef go quiet.

2. The Algae Takeover

Nature abhors a vacuum. On a dead reef, the vacuum is filled by fleshy macroalgae. Without healthy corals and with fewer herbivorous fish (which also decline), algae spread like a carpet, smothering any remaining coral and preventing new larvae from settling. The reef shifts from a vibrant, calcifying coral-dominated system to a soft, slimy algal-dominated one. This shift is often irreversible.

3. Collapse of the Physical Foundation

This is the most overlooked long-term impact. Living corals constantly add new limestone, building the reef framework. When they die, erosion takes over. Waves, boring organisms, and chemical processes break down the complex structure. What was once a cathedral of life becomes a flat, featureless rubble field within a few years. This loss of habitat complexity is the final nail in the coffin for most reef-associated species.

| Impact Stage | What Happens | Consequence for Marine Life |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Bleaching | Corals expel algae, turn white. | Corals starved, food web base disrupted. |

| Coral Mortality | Corals die, tissue gone. | Shelter and food sources vanish. |

| Structural Erosion | Limestone skeleton crumbles. | 3D habitat lost, species flee or die. |

| Regime Shift | Algae dominate the seascape. | Low-diversity, low-productivity system remains. |

The Human Cost: When Reef Services Fail

Reefs aren't just pretty to look at; they're critical infrastructure. Their decline hits human communities hard.

Coastal Protection: A healthy, complex reef absorbs up to 97% of a wave's energy. A flattened, dead reef does almost nothing. This increases coastal erosion, flooding, and damage from storms. The cost of replacing this service with artificial breakwaters is astronomical. Places like the Maldives or low-lying Pacific islands are literally on the front line.

Fisheries Collapse: An estimated 500 million people rely on coral reef fisheries for food and income. As fish populations crash, so do livelihoods. This isn't a future problem; it's happening now in parts of Southeast Asia and the Caribbean. The alternative? Overfishing deeper waters or turning to less sustainable practices.

Tourism Loss: Think of major dive destinations: the Great Barrier Reef, the Philippines, the Red Sea. Their economies are built on healthy reefs. A 2017 report by the Australian government's Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority highlighted that severe bleaching events directly threaten tens of thousands of tourism jobs. When the attraction dies, the town dries up.

Reef Recovery: Hope, Hype, and Hard Reality

You'll hear talk of "reef recovery." It's a hopeful term, but we need to be precise. Can coral grow back after a bleaching event? Yes, if conditions are perfect. But "recovery" rarely means returning to what was there before.

Recovery is often patchy and dominated by fast-growing, weedy coral species (like some Acropora). These are the "pioneer" species—they come back quick but are often the most vulnerable to the next heatwave. The slow-growing, massive corals that provide the most stable foundation might take decades or centuries to return, if they ever do.

The real danger is the shortening interval between bleaching events. According to research cited by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), mass bleaching events that used to be decades apart are now happening every 6 years on average. This doesn't give reefs time to recover. They get knocked down before they can stand back up.

What Divers Can Really Do (Beyond Just Not Touching)

Okay, so it's dire. But action is not futile. Divers are the eyes and advocates for the ocean. Your role is bigger than you think.

Be a Responsible Observer: On a bleached reef, buoyancy is non-negotiable. A stray fin kick on brittle, dead coral turns potential recovery sites into dust. Consider it a sacred space.

Choose Operators Who Advocate: Book with dive shops that actively support local marine protected areas, run reef restoration projects, or use their voice for policy change. Your money is a vote.

Citizen Science: Report your observations. Programs like Reef Check or local monitoring initiatives use diver data to track bleaching and recovery. That data is gold for scientists pushing for protection.

The Bigger Picture: Ultimately, reducing your carbon footprint and supporting policies that address climate change is the only solution to the root cause. But protecting reefs from local stressors (pollution, overfishing) gives them the best possible chance to withstand the global stress they cannot escape. It's about resilience.

Seeing a bleached reef changes you. It's a visceral lesson in interconnectivity. The white corals are just the first signal in a system-wide alarm. The real environmental impact of coral bleaching is the unraveling of a world—a process that, once set in motion, is heartbreakingly difficult to stop. But understanding that domino effect is the first step toward meaningful action.

Your comment