Quick Guide

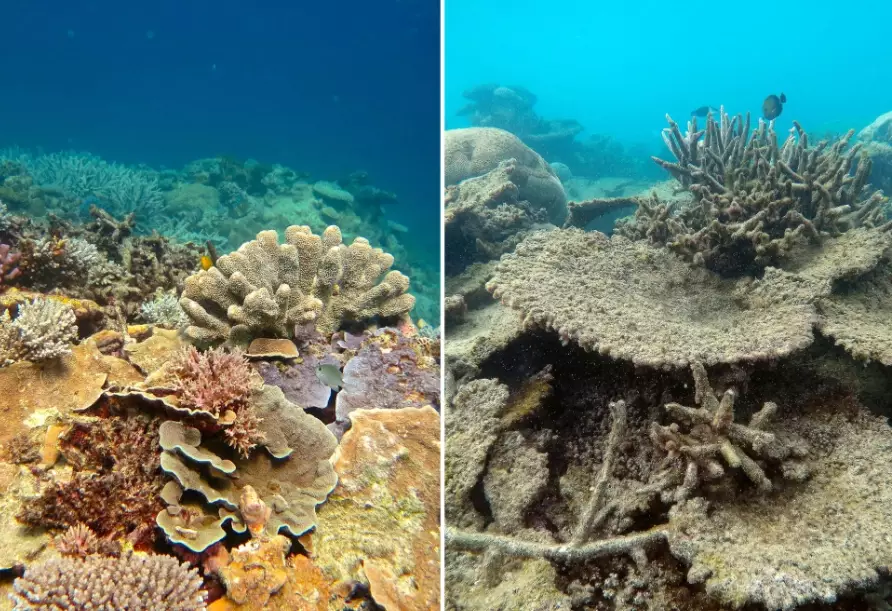

Let's talk about coral bleaching. You've probably seen the photos – those once vibrant, technicolor reefs now ghostly white, like underwater skeletons. It's a shocking sight. But here's the thing a lot of people miss: the bleaching itself, the coral turning white, is just the opening act. It's the symptom, not the full disease. The real story, the one that keeps marine biologists up at night, is what happens next. The effects of coral bleaching on marine ecosystems are like knocking over the first domino in an incredibly complex, city-wide setup. The crash just keeps going and going.

I remember the first time I saw a bleached reef up close while diving. It wasn't just the color, or lack thereof. It was the silence. The eerie, profound quiet. The fish were mostly gone. The usual hustle and bustle of the reef city had packed up and left. That emptiness hits you harder than the visual. That's the ecosystem collapsing.

In a nutshell: Corals are animals (polyps) that live in a symbiotic partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. The algae live inside the coral's tissues, give them their color, and through photosynthesis, provide up to 90% of the coral's energy. When stressed by things like high water temperatures, the coral expels these algae. Without them, the coral turns white (bleaches) and begins to starve. If the stress is brief, it can recover. If it lasts, the coral dies.

Why Should You Care? It's More Than Just Pretty Fish

Okay, so a bunch of underwater rocks lose their color. Big deal, right? Wrong. This is where we need to shift our thinking. Coral reefs are not just pretty scenery for snorkelers. They are the foundation. Think of a coral reef as the downtown business district, the hospital, the apartment complex, the grocery store, and the coastal defense wall of the ocean, all rolled into one. When it fails, everything that depends on it faces immediate trouble.

The effects of coral bleaching on marine ecosystems are profound because reefs support an insane amount of life. They cover less than 1% of the ocean floor but are home to about 25% of all marine species. That's like saying a single city block houses a quarter of the country's population. The density and interdependence are mind-boggling.

The Immediate Domino: When the Foundation Cracks

So the coral bleaches. The polyps are still there, but they're severely weakened, starving, and susceptible to disease. The structure is still there... for now. But the first wave of consequences starts fast.

The Food Web Shrinks Instantly. The zooxanthellae algae are a primary food source not just for the coral, but for a whole menagerie of tiny creatures. When that food source vanishes, the critters at the very bottom of the food chain scram or die off. This pulls the rug out from under small fish, which then affects bigger fish. It's a classic bottom-up collapse.

Architectural Integrity Fails. Live coral is constantly building and repairing the limestone skeleton. A bleached coral stops this maintenance. Boring organisms like certain worms and sponges start to break down the skeleton faster than it can be fixed. The reef structure, the very architecture of the ecosystem, becomes fragile and starts to crumble. This is a slow-motion disaster with fast consequences for anything that needs nooks and crannies to hide.

Think about it like this: if your apartment building's landlord stopped all maintenance, the plumbing would fail, the walls would crack, and it would become unsafe to live in long before it actually collapsed. That's the phase after bleaching – the slow, debilitating decline that makes the structure uninhabitable.

The Cascading Effects: Who Gets Hit and How

This is where it gets real. Let's break down the effects of coral bleaching on marine ecosystems by looking at the key residents and services of the reef city that get evicted or destroyed.

1. The Biodiversity Eviction Notice

Reefs are biodiversity hotspots. Bleaching serves a mass eviction notice. Fish that rely on coral for food (like butterflyfish that nibble on coral polyps) are the first to go. Then, the fish and invertebrates that depend on the complex 3D structure for shelter and hunting grounds follow. Parrotfish, crucial for cleaning algae off the reef, diminish. Without them, algae can smother any chance of coral recovery.

It's not just fish. Countless species of crabs, shrimp, sea stars, and mollusks lose their homes. The loss of this biodiversity isn't just a tragedy for nature lovers; it makes the whole system less resilient. A diverse ecosystem can withstand a shock better than a simple one. Bleaching strips away that resilience, making the next stressor even more deadly.

2. The Nursery Closes Its Doors

This is a huge one that often flies under the radar. Many commercially important fish species – including groupers, snappers, and some jacks – use coral reefs as nurseries for their juveniles. The maze of coral branches protects small fish from predators. When the coral dies and the structure collapses, these nurseries disappear. This leads to declining populations of these fish far out in the open ocean, directly impacting fisheries. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has extensive data linking healthy reefs to sustainable fish stocks, and the reverse is tragically true.

So, when you hear about effects of coral bleaching, remember it's hitting future fish populations across vast areas of the sea.

3. The Ripple Effect to Connected Habitats

Reefs don't exist in a vacuum. They're connected to seagrass beds and mangrove forests. Many species use all three at different life stages. The health of one affects the others. A collapse on the reef can mean increased pressure on seagrass beds as displaced species move in, potentially overgrazing. Mangroves, which often buffer the coast near reefs, can face changed sediment and water flow patterns if the offshore reef barrier degrades. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) consistently highlights this interconnectedness in its reports on marine ecosystem health.

4. The Coastal Defense Wall Crumbles

This effect hits humans directly. Coral reefs act as natural breakwaters. They absorb up to 97% of wave energy from storms, hurricanes, and tsunamis, protecting coastlines, beaches, and the millions of people who live behind them. As bleaching kills coral and the structure erodes, this protective service diminishes. Coastal communities face increased risk of flooding, erosion, and property damage. The value of this service is in the billions of dollars annually. Losing it isn't just an ecological problem; it's a direct economic and safety threat. The World Resources Institute has detailed analysis on the coastal protection value of reefs, and it's staggering.

We're talking about real-world consequences for villages and cities. It's not abstract.

From Ecosystem Effects to Human Realities

Let's get practical. What do these effects of coral bleaching on marine ecosystems mean for people? It translates into three major areas: food, money, and safety.

Food Security Takes a Hit. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide rely on reef-associated fisheries as a primary source of protein. When fish populations crash due to habitat loss, it creates a food security crisis. This is especially acute in developing nations and small island states where alternatives are limited.

The Tourism Industry Suffers. People don't pay big money to go diving or snorkeling on a graveyard of white, dead coral. Reef-based tourism is a multi-billion dollar global industry. Widespread bleaching events have already caused significant losses in places like the Great Barrier Reef, where operators have had to shift tours to less-affected areas, which isn't always possible. I've spoken to dive shop owners who've had to completely rethink their business model after a major bleaching event wiped out their local sites. The despair is palpable.

Coastal Vulnerability Skyrockets. As mentioned, with the reef's buffering capacity reduced, the cost of coastal infrastructure protection and disaster recovery climbs. Governments and insurance companies are starting to factor reef loss into their risk models, and the numbers are not pretty.

| Impact Sector | Primary Consequence | Human & Economic Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Fisheries | Collapse of reef-associated fish stocks; loss of nursery habitats. | Loss of livelihood for fishers; increased food prices & protein scarcity for coastal communities. |

| Tourism | Degradation of the primary aesthetic and ecological attraction. | Loss of tourism revenue, business closures, job losses in hospitality & guiding sectors. |

| Coastal Protection | Reduced wave energy absorption leading to increased erosion & flooding. | Billions in infrastructure damage, loss of land, increased insurance costs, community displacement. |

| Medical Research | Loss of biodiversity reduces potential for discovery of new marine-derived compounds. | Potential future cures for diseases like cancer may be lost before discovery. |

See? It's all connected. The ecological dominoes eventually knock over the human economic ones.

Is There Any Hope? What's Being Done?

After all that doom and gloom, it's fair to ask: is it all hopeless? Not entirely, but we have to be brutally honest. The primary driver of mass bleaching is climate change-induced ocean warming. No local action can fully stop a marine heatwave. So, the number one, non-negotiable solution is drastic global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Everything else is basically emergency medicine and physical therapy while we (hopefully) treat the underlying disease.

That said, local actions are the emergency medicine, and they are crucial. They can buy time, help reefs recover, and maintain pockets of resilience. Here's what that looks like on the ground (or in the water):

- Reducing Local Stressors: This is huge. A reef stressed by pollution, overfishing, or physical damage is much more likely to bleach and die when a heatwave hits. A healthy reef has a better shot. So, improving water quality by managing land-based runoff (sewage, agricultural chemicals), establishing and enforcing no-take marine protected areas (MPAs), and preventing destructive fishing practices are all essential. Organizations like the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force coordinate many of these local efforts.

- Coral Gardening and Restoration: This is the hands-on stuff you might see in documentaries. Scientists and volunteers grow coral fragments in nurseries and then outplant them onto degraded reefs. It's labor-intensive, expensive, and can feel like trying to refill an ocean with a teaspoon during a storm. But for high-value, critically important reefs (like those protecting a specific coastline or supporting a key community), it can be a vital tool. The success rates are mixed, and it's no silver bullet, but it's part of the toolkit.

- Assisted Evolution: This is the cutting-edge, controversial frontier. Researchers are trying to identify and breed coral strains that are more thermally tolerant. The idea is to give evolution a helping hand to keep pace with rapidly changing conditions. It raises big ethical and ecological questions – are we creating a monoculture? What are the unintended consequences? – but in desperate times, desperate measures are considered. The work led by institutions like the Australian Institute of Marine Science is fascinating but still in early stages.

The Bottom Line on Solutions: Global climate action is the only real cure. Local protection and restoration are the critical life support systems that keep the patient alive while we work on the cure. We need to be doing both, aggressively and simultaneously. Pretending local action alone will solve it is naive. Giving up because the global problem is hard is a death sentence.

Your Burning Questions, Answered

I get a lot of questions about this topic. Here are some of the most common ones, straight from conversations I've had with concerned folks.

Can a bleached coral recover?

Yes, it can, but only if the stressor (like high temperature) is removed quickly. If the water cools and the coral polyps haven't starved to death, they can slowly re-acquire zooxanthellae and regain their color and function. This recovery takes energy and time, and leaves the coral weakened. Repeated bleaching events, which are becoming more common, don't give them that recovery time. It's like recovering from a serious illness only to immediately catch another one – eventually, your body gives out.

Does all coral bleaching lead to death?

No, not all. But the severity and duration of the thermal stress determine the outcome. A mild, short-lived event might cause partial bleaching and high recovery. A severe, prolonged marine heatwave causes mass mortality. The problem is that with climate change, we're seeing more of the severe, prolonged kind. The Great Barrier Reef, for instance, has suffered mass bleaching events in 2016, 2017, 2020, and 2022. That frequency is unprecedented.

What's the single biggest cause of coral bleaching?

Elevated sea surface temperatures due to climate change are the primary, large-scale driver. Think of it as the main weapon. However, other stressors act as force multipliers: local pollution, sedimentation from coastal development, and ocean acidification (also caused by excess CO2) which weakens coral skeletons. But the heat is the trigger for the mass, global events we're now witnessing.

Are some corals more resistant than others?

Absolutely. Some species are tougher than others. Massive, boulder-shaped corals tend to be more resistant than delicate, branching corals. But even the tough ones have their limits. The real worry is that bleaching events are now so severe and frequent that they are overwhelming even the historically resistant species. We're seeing mortality in corals that were once considered bulletproof.

Look, writing about the effects of coral bleaching on marine ecosystems is depressing. There's no sugar-coating it. The scale of the loss is monumental. But understanding the full, cascading impact – not just the white corals, but the silent reefs, the collapsing fisheries, the more vulnerable coastlines – is the first step towards mobilizing real, meaningful action. It's not just about saving pretty fish. It's about preserving the foundational infrastructure of a quarter of the ocean's life, and by extension, protecting the food, jobs, and safety of hundreds of millions of people. That's a story worth telling, and more importantly, a problem worth solving.

We have to stop seeing reefs as just a vacation backdrop. They are active, vital, struggling metropolises. And their fate is inextricably linked to ours.

Your comment