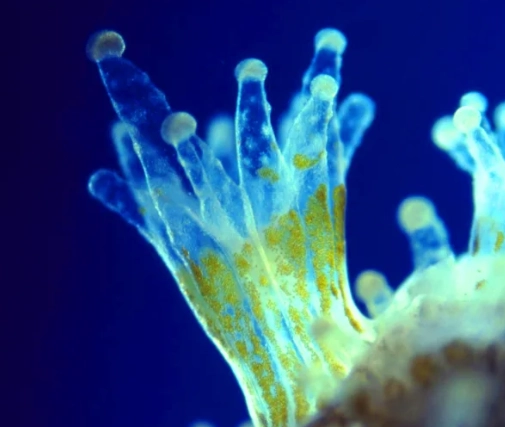

I remember the first time I saw it under a microscope. I was on a research vessel, looking at a sliver of coral tissue. The coral polyps were fascinating, but the real show was inside them: thousands of tiny, golden-brown spheres, each pulsing with life. Those were the zooxanthellae (pronounced zo-zan-THEL-ee), and in that moment, the abstract concept of symbiosis became vividly real. This isn't just a biological curiosity; it's the fundamental deal that built the Great Barrier Reef, the reefs of the Caribbean, and every other shallow, sun-drenched coral ecosystem on the planet. Get this relationship wrong, and the entire vibrant city of the reef collapses into a ghost town.

Most people see a coral and think "animal." That's only half the story. It's more accurate to think of a coral polyp as a solar-powered apartment building. The animal builds the structure (the calcium carbonate skeleton), but inside its soft tissue live millions of microscopic algal tenants. These tenants, the zooxanthellae, pay their rent in sugar, and that sugar runs the entire operation.

What's Inside?

The Biological Bargain: What Each Partner Brings

Let's break down this partnership without the textbook jargon. It's a trade, pure and simple.

The Coral's Job (The Landlord & Bodyguard):

The coral polyp provides prime real estate. It gives the algae a safe home inside its own cells, positioned right where sunlight can pour in. More importantly, it supplies the algae's favorite fertilizer: its own waste products. Think ammonia and carbon dioxide—stuff the coral needs to get rid of, and stuff the algae craves to grow. The coral's tissue also protects the algae from being eaten by plankton grazers. It's a secure, nutrient-rich, sunlit apartment, rent-free.

The Zooxanthellae's Job (The Solar Power Plant & Sugar Factory):

Using sunlight, the algae photosynthesize. They take that CO2 and those waste nutrients and convert them into organic compounds—mainly sugars (glycerol, glucose) and amino acids. Here's the kicker: they leak up to 95% of this produced food directly into the coral's tissue. This energy transfer is staggering. It's estimated that for every square centimeter of coral, the zooxanthellae produce enough energy to power the coral's needs for growth, reproduction, and building that heavy limestone skeleton.

This is why tropical reef-building corals can grow so rapidly in nutrient-poor waters. The water is clear because there's little plankton, but the coral doesn't care. It has its own internal farm. The brilliant colors of many corals? Those are often from pigments in the zooxanthellae themselves, or fluorescent proteins the coral produces to optimize light for its tenants.

When the Deal Breaks Down: The Science of Coral Bleaching

Now for the hard part. This partnership is stable, but it's fragile. It operates within a very narrow Goldilocks zone. When the environment gets too far out of that zone, the deal sours, fast.

The textbook says: "Coral bleaching is the expulsion of zooxanthellae due to stress." That's correct, but it misses the drama. It's not a calm eviction. It's a toxic breakdown.

Here's what happens at the cellular level, something I wish more articles explained:

- The Stressor Hits: Usually, it's elevated water temperature. Even 1°C above the seasonal average for a few weeks can trigger it. The heat damages the photosynthesis machinery inside the algal cell.

- Production Turns Toxic: The damaged machinery starts leaking electrons. This leads to the creation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—think of them as cellular bleach. They're highly destructive molecules.

- The Host Panics: These toxic ROS leak from the algae into the coral's own tissue. The coral cell is now under oxidative attack from its own tenant.

- Eviction or Digestion: To save itself, the coral has two options. It can forcibly expel the algal cell, or it can digest it. Either way, the algae are gone.

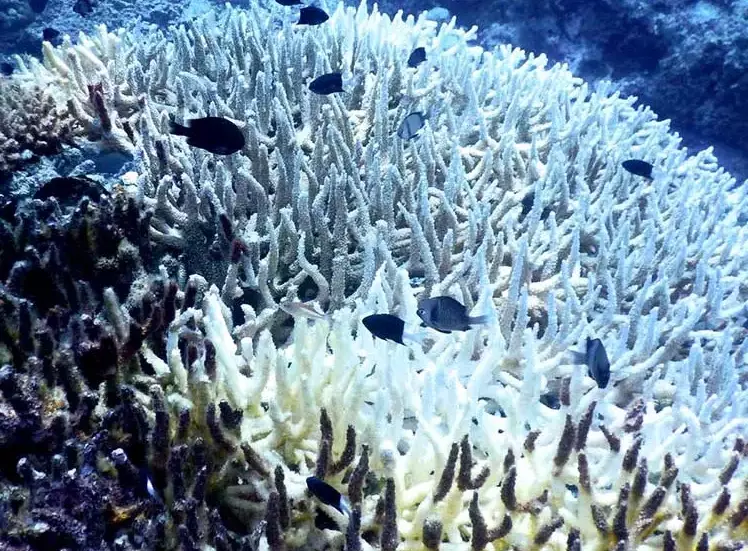

With the algae gone, the coral's tissue becomes transparent. You see straight through to the white calcium carbonate skeleton beneath. The coral isn't dead yet, but it's starving. It's lost 90% of its energy supply. It can try to catch plankton with its tentacles at night, but it's like trying to run a marathon on a single cracker.

If conditions cool down quickly, some algae can be reabsorbed from the water. But if the stress lasts too long, the coral will die from disease or outright starvation. Then, filamentous algae move in to cover the skeleton, and the reef structure begins to erode.

It's Not Just Heat: The Other Relationship Killers

While heat is the global headline, other local stressors act like constant arguments that make the partnership brittle, so when heat comes, it's the final straw.

Sediment & Turbidity: Muddy water from coastal construction or poor land use blocks sunlight. The algae can't photosynthesize. The coral, not getting its sugar rent, may reduce algal numbers or expel some. It's like the landlord turning off the electricity because the tenant isn't paying.

Nutrient Pollution: This one is counterintuitive. Sewage and fertilizer runoff add nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus) to the water. You'd think more fertilizer would help the algae, right? It does—too much. The algae populations inside the coral can explode, throwing the careful balance off. Or, it fuels the growth of external macroalgae that smother the coral. It upsets the delicate nutrient economy of their deal.

Chemical Sunscreens: Certain common UV-filtering chemicals (like oxybenzone and octinoxate) have been shown in studies to cause bleaching in lab settings. They can awaken viral infections in the zooxanthellae or act as endocrine disruptors for the coral. While the scale of impact is debated, in high-traffic tourist areas, it's considered a contributing stressor.

A reef dealing with chronic murky water and pollution is a reef already on the edge. A minor heatwave then becomes catastrophic.

Can the Partnership Be Saved? Looking at the Future

This is where the science gets fascinating, and a bit hopeful. Researchers are looking at ways to make this symbiosis more resilient.

One avenue is assisted evolution. Some coral species, and even some individual colonies, naturally host slightly different types (clades) of zooxanthellae. Some of these algal types are more heat-tolerant than others. Scientists are exploring if we can selectively breed or condition corals to associate with these "hardier" algae. It's like helping the coral find a tenant who can handle a hotter apartment.

Another approach is identifying and propagating "super corals." These are colonies that have survived severe bleaching events on natural reefs. They might have more efficient mechanisms to deal with oxidative stress, or they might already host resilient algae. Projects are underway to grow fragments of these survivors in nurseries and outplant them to repair damaged reefs.

But let's be clear: these are local tools, not global fixes. They're like developing a better fireproof material while the planet's thermostat is still rising. The only real solution is to reduce the global stressors—climate change and ocean acidification—while ruthlessly eliminating the local ones like pollution and overfishing. The partnership needs a stable environment to thrive.

What You Can Do: A Diver's and Ocean Lover's Perspective

You don't need a PhD to help. If you dive or snorkel, you're a direct witness. Your actions matter.

- Be Buoyant Perfect: A single fin kick on a coral can damage the tissue, breaking the delicate layer where the algae live. Master your buoyancy. It's the number one rule for reef conservation.

- Choose Reef-Safe Sun Protection: Opt for mineral-based sunscreens (zinc oxide, titanium dioxide) that are "non-nano" and labeled reef-safe. Better yet, wear a rash guard and hat.

- Support the Right Businesses: Choose dive operators and resorts that have clear environmental policies: proper wastewater treatment, mooring buoys instead of anchors, and education for guests.

- Become a Citizen Scientist: Organizations like Reef Check train divers to collect valuable data on reef health, including bleaching events. Your observations can contribute to global science.

- Talk About the Algae: When you share photos, don't just say "beautiful coral." Mention the hidden partnership that makes it possible. Understanding fosters care.

Your Burning Questions Answered

Can corals survive without their algae partners?

What water temperature is too hot for the coral-algae relationship?

If a coral turns white, is it immediately dead?

Can we add zooxanthellae back to bleached corals to save them?

The story of zooxanthellae and coral is the story of collaboration at its most fundamental. It's a reminder that the most spectacular things in nature are often built on unseen, delicate partnerships. When we understand that the vibrant reef in front of us is actually a living metropolis powered by billions of microscopic solar panels, it changes how we see it. It's not just a pretty place to dive. It's a breathtakingly complex and fragile achievement of life. And right now, that achievement needs all the help it can get.

Your comment