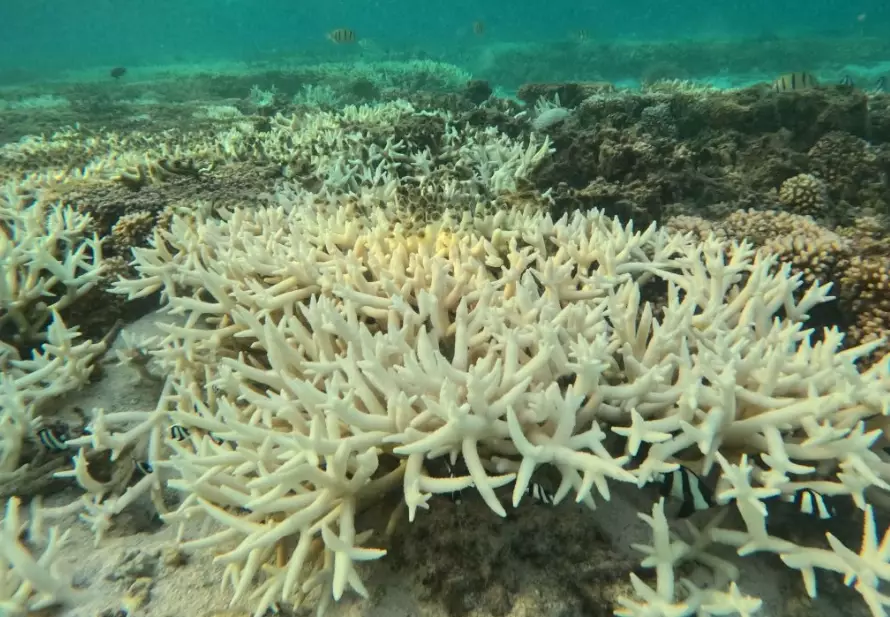

You've seen the photos. Vast stretches of coral reef, once a kaleidoscope of vibrant purples, greens, and oranges, now stark, ghostly white. Coral bleaching. The term gets thrown around a lot, but its root cause is a microscopic divorce. At the heart of this ecological tragedy is the breakdown of one of the ocean's most successful relationships: the symbiosis between coral animals and their algal tenants, zooxanthellae.

If you want to understand bleaching, you can't just stop at "the water got too hot." You have to dive into the cellular level, into the daily life of a coral polyp and its millions of photosynthetic roommates. That's where the story really begins—and where it falls apart.

What You'll Discover

- What Exactly Are Zooxanthellae? (They're Not Plants)

- The Symbiotic Deal: A Perfect Trade Agreement

- How Stress Triggers the Breakup

- The Bleaching Process: Expulsion, Not Death

- It's Not Just Heat: Other Stressors That Harm the Partnership

- Can the Coral Recover? The Path Back from the Brink

- What This Means for You: A Diver's Perspective

What Exactly Are Zooxanthellae? (They're Not Plants)

Let's clear something up first. Calling zooxanthellae (pronounced zoo-zan-THEL-ee) "tiny plants" living inside coral is technically wrong, and that misconception leads to confusion. They're actually a type of dinoflagellate, a single-celled alga. Think of them more as super-powered, solar-fueled microbes.

They live inside the coral polyp's own cells, in a special compartment. Each coral polyp might host thousands of these algal cells. The coral doesn't just tolerate them; it actively manages the relationship, controlling how many algae it hosts and even digesting some if it needs a quick energy boost.

It's a tightly regulated, intimate cohabitation.

The Symbiotic Deal: A Perfect Trade Agreement

This isn't charity. It's a strict, mutually beneficial business deal. Here’s the exchange:

The Coral Provides:

A Safe Home & Prime Real Estate: Protection from predators inside the polyp's tissues.

Waste Products: Carbon dioxide and nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus (from its metabolic waste), which are fertilizer for the algae.

Access to Sunlight: By building complex skeletal structures, corals position their algal partners in the sunlit shallow waters.

The Zooxanthellae Provide:

Up to 90% of the Coral's Energy: Through photosynthesis, they make sugars, glycerol, and amino acids, leaking a large portion directly to the coral host.

Oxygen: A byproduct of photosynthesis.

Brilliant Colors: The pigments in the algae (chlorophyll and others) are what give most corals their famous colors. The coral's own tissue is mostly translucent.

This deal is why coral reefs can thrive in crystal-clear, nutrient-poor tropical waters. They create their own food factory internally. Without zooxanthellae, the energy cost of building those massive limestone skeletons would be impossible for most reef-building corals.

How Stress Triggers the Breakup

The partnership is stable, but fragile. It operates best within a narrow range of conditions. When the environment shifts outside that comfort zone, the deal starts to sour. The primary stressor is elevated sea temperature.

Here’s the nuanced part most summaries miss: The heat itself isn't directly killing the coral or the algae at first. Instead, it disrupts the photosynthesis process inside the zooxanthellae. Think of it like a solar panel overheating and starting to produce dangerous sparks instead of clean electricity.

Under heat stress, the photosynthetic machinery produces an overload of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—essentially, toxic byproducts. These ROS leak into the coral polyp's cell, causing oxidative damage. It's like your tenant's factory suddenly starts leaking acid into your house.

The coral, sensing this cellular damage, has a choice: continue housing a damaging tenant or evict it. To save itself, it chooses eviction. It's a survival tactic, albeit a desperate one.

The Bleaching Process: Expulsion, Not Death

This is critical. Bleaching is the expulsion of the zooxanthellae, not the death of the coral. When the coral forces out a significant portion of its algal partners, you see the white limestone skeleton through its now-transparent tissue. The colorful pigments were in the algae; with them gone, only the white skeleton shows.

The coral is still alive at this point. But it's in critical condition. It's just lost its primary food source. It can try to feed more actively on plankton with its tentacles, but that's like trying to replace a full-time salary with a few odd jobs. It's not sustainable.

If the stressful conditions—like warm water—subside quickly, the coral can slowly recruit new zooxanthellae from the few that remained or from the surrounding water. Recovery is possible.

If the stress persists for weeks or months, the coral will literally starve to death. Its tissue dies and sloughs off, leaving behind the bare, white skeleton, which will quickly be overgrown by algae.

It's Not Just Heat: Other Stressors That Harm the Partnership

While thermal stress is the global headline-maker, the symbiotic relationship is sensitive to a suite of insults. Any of these can trigger the same toxic ROS production and lead to eviction:

Cold Water: Yes, corals can bleach from cold snaps too, though it's less common.

Excess Sunlight (Solar Irradiance): Intense UV radiation, especially when combined with warm water, is a double whammy.

Pollution & Sedimentation: Runoff from land smothers corals, blocks sunlight, and introduces chemicals that disrupt cellular functions. Nutrient pollution (e.g., from fertilizers) can fuel algal blooms that further smother reefs.

Freshwater Influx: Heavy rainfall or runoff lowers salinity, shocking the coral's cells.

Ocean Acidification: While not a direct bleaching trigger, it weakens the coral's skeletal structure, adding another layer of stress that makes it harder to cope with warming. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tracks these combined stressors closely.

Often, it's a combination of these factors that pushes a reef over the edge.

Can the Coral Recover? The Path Back from the Brink

Recovery isn't a simple on/off switch. It's a slow, energy-intensive process that leaves the coral vulnerable. Think of a person recovering from a major illness—they're alive, but weak and susceptible to other infections.

During recovery, the coral must:

1. Acquire new zooxanthellae. These can come from residual populations or from the water. Some evidence suggests corals may take in types of zooxanthellae that are more heat-tolerant after a bleaching event, a tiny bit of natural adaptation.

2. Rebuild its energy reserves. Growth and reproduction are put on hold. All energy goes to basic survival.

3. Fight off disease. A stressed, bleached coral is a prime target for pathogens.

The problem today is the frequency of events. Corals need years of stable conditions to fully recover. According to reports like those from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, mass bleaching events are now hitting some reefs repeatedly within a decade, giving them no time to bounce back. This is what leads to ecosystem collapse, not a single bleaching event.

What This Means for You: A Diver's Perspective

I remember diving a site in Southeast Asia years ago that was famed for its soft coral gardens. When I returned recently, it was a monochrome landscape. It wasn't just sad; it felt wrong. The silence was the weirdest part—less clicking, fewer fish. The entire food web was disrupted.

Understanding the zooxanthellae-coral bond changes how you see a reef and how you act around it.

Your buoyancy matters more than you think. A fin kick that clouds sediment onto a coral blocks the sunlight its remaining zooxanthellae desperately need during a fragile recovery phase.

Chemical sunscreens are a direct assault. Compounds like oxybenzone can induce the same toxic oxidative stress in zooxanthellae that warm water does. Wearing a rash guard or using mineral-based sunscreen isn't just a suggestion; it's removing a direct local stressor.

You become a witness. Divers are the eyes on the reef. Noticing early signs of bleaching (paling before full whiteness) and reporting it to local marine park authorities through citizen science apps can contribute to larger monitoring efforts.

The relationship between zooxanthellae and coral is the engine of the reef. Bleaching is that engine seizing up. By understanding it at this fundamental level, we move beyond just knowing it's bad to understanding why it's so catastrophic and how our actions, global and local, directly impact that delicate intracellular partnership.

Your comment