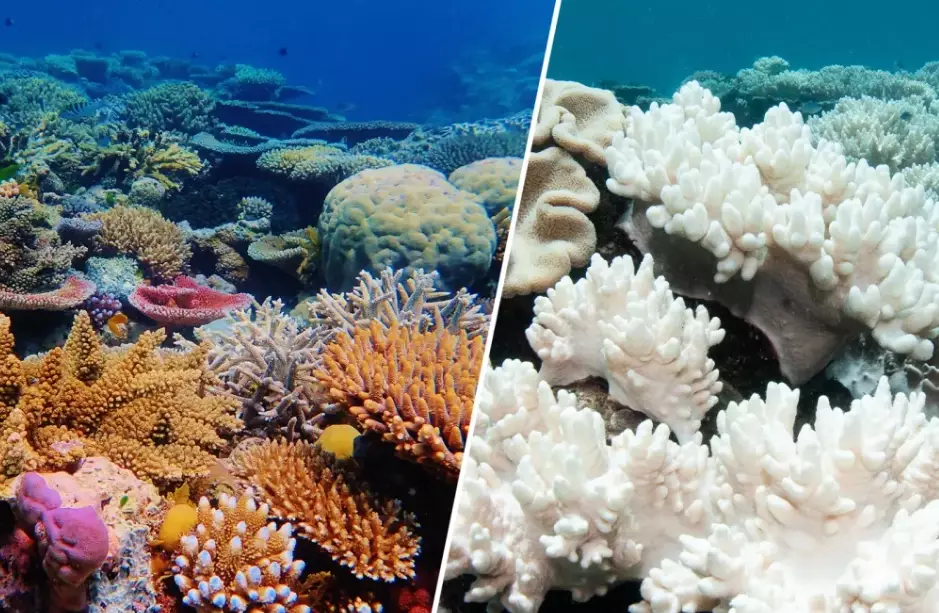

You're hovering over a reef, expecting a burst of color, but instead you see a landscape of ghostly white skeletons. It's a sight that's becoming tragically common. Coral bleaching isn't just about color loss—it's a desperate survival move. At its heart, bleaching happens when corals kick out their microscopic roommates, the zooxanthellae algae. But why would they evict their main food source? The answer is stress. Overwhelming, life-threatening stress.

What You'll Learn

The Symbiotic Lifeline: Corals and Zooxanthellae

First, let's clear up a huge misconception. A coral isn't just a rock or a plant. It's an animal—a polyp—that forms a partnership so tight it blurs the line between species. Millions of tiny zooxanthellae (pronounced zoo-zan-THEL-ee) algae live inside the coral's transparent tissue.

Think of it like this: the coral provides a secure, sunny apartment (its tissue) and a steady supply of carbon dioxide. The algal tenant pays rent in the form of sugars and other nutrients, which it produces through photosynthesis. This sugar is the coral's primary energy source, fueling up to 90% of its needs. It's why coral reefs can thrive in crystal-clear, nutrient-poor tropical waters—they bring their own food factory.

The vibrant colors of a healthy reef? Mostly from the pigments of these algae. The coral itself is mostly see-through.

The Primary Culprit: Thermal Stress and Ocean Warming

Ask any marine biologist the main cause of mass bleaching events, and the answer is unequivocal: abnormally high sea surface temperatures. This isn't about a pleasant warm bath. It's about sustained heat that pushes corals past their limit.

The mechanism is biochemical chaos. Elevated water temperature disrupts the photosynthesis machinery inside the zooxanthellae. It starts producing reactive oxygen species (ROS)—think of them as toxic byproducts. In small amounts, the coral can manage them. But when the heat is on, ROS production goes into overdrive.

This toxin floods the coral's tissues. It's like your food factory suddenly pumping poison into your home. The coral has no choice. To save itself from this internal poisoning, it forcibly expels the algae. The tenant is evicted, the food supply is cut, and the color vanishes, revealing the stark white calcium carbonate skeleton beneath.

It's not just a degree or two. Scientists use a metric called "Degree Heating Weeks" (DHW), tracked by organizations like NOAA's Coral Reef Watch. One DHW equals one week of sea surface temperatures one degree Celsius above the usual summer maximum. Corals start feeling the heat around 4 DHW. At 8 DHW, widespread bleaching is likely. I've seen reefs in the Philippines hit 12+ DHW, and the effect was total—a white desert as far as you could swim.

The scary part? These heatwaves are now more frequent, longer, and more intense due to climate change. Reefs don't get time to recover.

Beyond Heat: Other Stressors That Trigger Bleaching

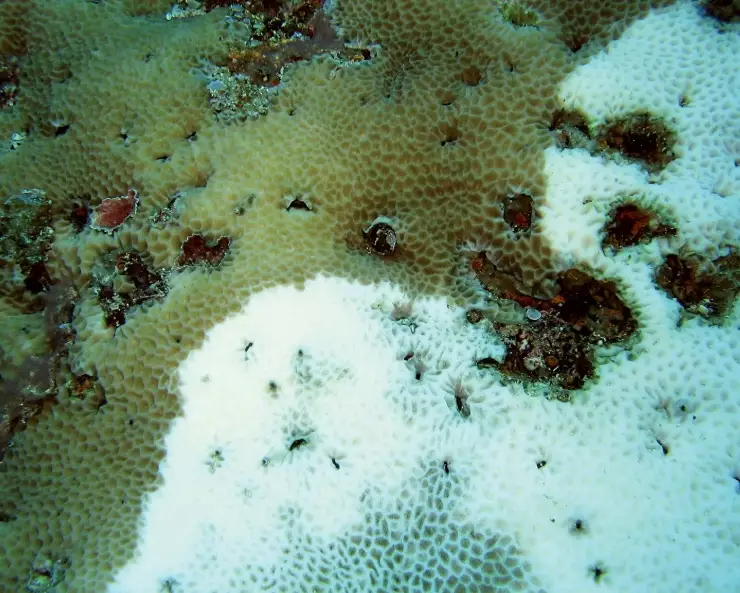

Heat gets the headlines, but it's rarely acting alone. Corals face a barrage of insults, and they all converge on the same stressful outcome: expelling zooxanthellae. A common mistake is to blame every white patch on warm water. Look closer. The pattern often tells the story.

Localized Anthropogenic Stressors

These are the human-made problems that weaken corals day in, day out, making them far more susceptible to the next heatwave.

| Stress Factor | How It Causes Stress | What You Might See |

|---|---|---|

| Sediment Runoff | From coastal construction or deforestation. Smothers corals, blocks sunlight needed for photosynthesis. | Bleaching concentrated near river mouths or dredging sites. Corals covered in a layer of silt. |

| Nutrient Pollution | From sewage or agricultural fertilizer. Fuels algal blooms that outcompete and shade corals. | Murky water, excessive seaweed growth alongside bleached corals. |

| Chemical Pollution | Heavy metals, pesticides, and notably, certain sunscreen chemicals (oxybenzone, octinoxate). | Can act as direct toxins or hormone disruptors, triggering expulsion. Often seen in popular snorkeling coves. |

| Physical Damage | Anchors, diver contact, fishing gear. Breaks the coral's protective tissue, inviting disease and demanding huge energy to repair. | Bleaching and tissue death in specific, damaged patches or along a scrape line. |

Global Climate Drivers

These are the large-scale climate phenomena that compound the problem.

Ocean Acidification: As the ocean absorbs more CO2, it becomes more acidic. This makes it harder for corals to build their skeletons. A stressed, energy-starved coral from bleaching combined with a more acidic environment is a recipe for reef collapse. The coral can't rebuild.

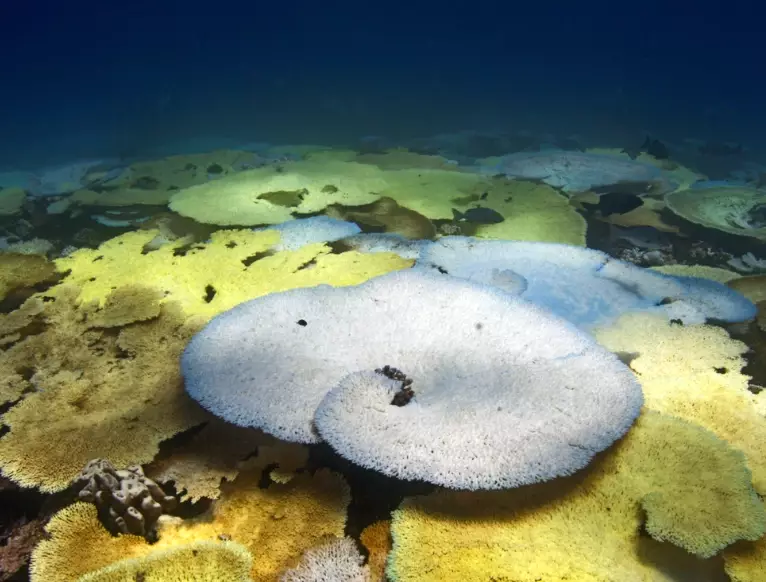

Intense Solar Irradiance: Especially UV radiation. On a calm, hot day with clear skies, the double whammy of heat and intense sunlight can be devastating. It supercharges that toxic ROS production in the algae.

Cold Water Shock: Less common, but yes, sudden drops in temperature (like from upwelling events) can also shock the symbiosis and cause bleaching.

What Happens During and After a Bleaching Event?

The moment of expulsion is a point of no return for that partnership. The coral is now running on empty, metabolizing its own tissue and any stored lipids. It's in survival mode.

Recovery is possible, but it's a gamble. If the stressful conditions subside within a few weeks, some zooxanthellae (either from the water or those remaining at low levels) can repopulate the coral. Color slowly returns. But the coral is emaciated. Its growth stops. Its ability to reproduce plummets. It's far more vulnerable to disease—the white skeleton is a perfect canvas for opportunistic algae or bacteria to take over, often turning the coral black or green, which usually means it's dead.

If the stress lasts for months, or if it's a repeated annual event, the coral simply starves to death. The tissue dissolves, leaving nothing but the limestone skeleton, which will eventually erode.

The 2016-2017 global bleaching event, documented by the IUCN, affected over 90% of the Great Barrier Reef. Vast stretches experienced catastrophic mortality. Recovery in those areas is measured in decades, assuming no further major bleaching—an assumption that seems optimistic.

Can We Help Corals Survive Bleaching?

This is the million-dollar question. The ultimate solution is slashing global carbon emissions to curb ocean warming and acidification. That's the non-negotiable, big-picture fight.

But local action is critical for buying time and building resilience. It's about removing the other stressors so corals are healthier when a heatwave hits.

On a Policy Level: Creating strong marine protected areas (MPAs) that limit fishing and pollution. Improving wastewater treatment. Regulating coastal development to minimize runoff. Banning particularly harmful sunscreen ingredients, as places like Hawaii and Palau have done.

On a Personal Level (Especially for Divers & Tourists):

- Master Neutral Buoyancy: This is the single most important skill. Never touch, stand on, or kick the reef. A fin swipe causes a local bleaching scar that can take years to heal.

- Choose Reef-Safe Sunscreen: Look for mineral-based blockers like non-nano zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. Avoid oxybenzone and octinoxate. Better yet, wear a rash guard and avoid sunscreen on large parts of your body.

- Support Sustainable Operators: Choose dive shops and resorts with clear environmental policies, like mooring buoys (instead of anchoring), responsible waste management, and education programs.

- Be a Voice: Share what you've seen. Responsible tourism creates economic value for healthy reefs, which incentivizes protection.

Scientists are also exploring more direct interventions—like assisted evolution to breed more heat-tolerant corals, or deploying shade cloths over critical reef areas during heatwaves. These are promising but costly band-aids. They won't work if the ocean keeps warming.

Seeing a bleached reef changes you. It's silent and shocking. Understanding that it's a stress response, a desperate attempt to survive poisoning from its own partners, makes it even more tragic. It's a complex biological process with one simple root cause: we've pushed the reef's environment too far. Reversing that is the only way to ensure corals stop expelling their zooxanthellae and keep our oceans brilliantly colorful.

Your Coral Bleaching Questions, Answered

Can bleached corals recover if water temperatures return to normal?

Yes, but it's a fragile and energy-intensive process. Recovery depends on the severity and duration of the stress. If conditions improve quickly (within weeks), some corals can slowly re-acquire zooxanthellae from the water column. However, prolonged bleaching exhausts the coral's energy reserves. Even if it survives, the coral is weakened, more susceptible to disease, and may experience reduced growth and reproduction for years. Think of it as a patient recovering from a severe illness—they survive, but they're not the same for a long time.

Is coral bleaching the same as coral death?

This is a critical distinction many miss. Bleaching is a stress response, not immediate death. The coral animal is still alive, but it's starving. Without its algal partners, a coral can only survive for a limited time—typically a few weeks to a couple of months, depending on the species and its stored energy. If the stress is removed in time, recovery is possible. If not, the coral will eventually die from starvation, often followed by algae overgrowth that turns it green or black. So, bleaching is a severe warning sign, a cry for help, not an obituary.

Besides warm water, what else can trigger coral bleaching?

While heat is the global headline, local stressors are brutal accomplices. Cold water snaps can also cause bleaching. More commonly, pollution is a major trigger. Sediment runoff from coastal development smothers corals and blocks sunlight. Excess nutrients from agricultural fertilizers or sewage fuel algal blooms that also shade corals. Even common sunscreen chemicals like oxybenzone can act as a direct toxin, disrupting the coral's biology and triggering expulsion. On a dive trip, you might see a reef bleached in a patchy pattern downstream from a river outlet or a popular swimming area—that's often the fingerprint of localized pollution, not just a warm current.

As a diver or tourist, what's the single most important thing I can do to prevent causing stress to corals?

Perfect your buoyancy and never touch. Physical contact from fins, hands, or gear scrapes off the coral's delicate mucus layer, creating an open wound that is an entry point for disease and a massive local stress event. It's like ripping off your skin while you're fighting a fever. Secondly, choose mineral-based (zinc oxide/titanium dioxide) sunscreens labeled "reef-safe" and apply them well before entering the water. The biggest impact, however, comes from your choices on land: reducing your carbon footprint and supporting sustainable seafood and businesses that protect coastal areas.

Your comment