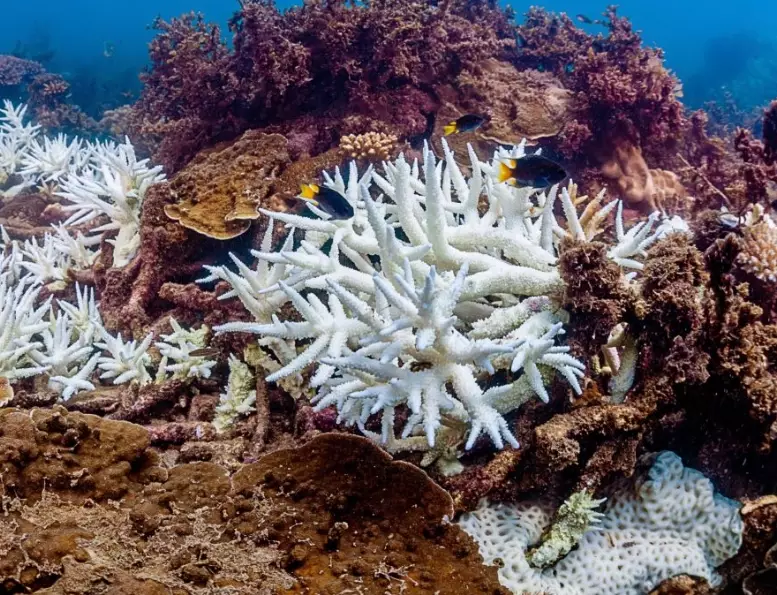

You see the photos all the time. A vibrant, technicolor reef one year, a ghostly white graveyard the next. Coral bleaching events are making headlines with alarming frequency. The immediate reaction is often despair. It looks like death. It feels final.

But here's the thing the headlines often miss: a bleached coral isn't necessarily a dead coral.

Reversal is possible. Recovery happens. The question isn't just "can it be reversed?" but "under what conditions, and how can we tip the scales in the coral's favor?" The answer is a complex mix of marine biology, climate science, and hard-nosed conservation work. Let's cut through the doom and get into the practical reality of bringing reefs back from the brink.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

What Exactly Is Coral Bleaching? (It's Not What You Think)

First, a crucial correction. When a coral bleaches, the animal isn't dead. Not yet.

Corals are animals—tiny polyps—that live in a partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. The algae live inside the coral's tissue. They photosynthesize, providing up to 90% of the coral's food. In return, the coral gives them a protected home and nutrients. It's one of the ocean's great partnerships.

Bleaching is a breakup.

When the coral gets stressed, primarily by prolonged high water temperatures, the partnership breaks down. The coral expels its algal tenants. Since the algae give the coral its color (browns, greens, yellows), the coral's white limestone skeleton shows through the transparent tissue. Hence, it looks "bleached."

The primary stressor is heat. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), when water temperatures stay just 1°C above the usual summer maximum for several weeks, bleaching can start. At 2°C above, widespread bleaching and mortality begin. But heat isn't the only culprit. Severe cold snaps, extreme low tides that expose corals, pollution, and freshwater runoff can also trigger bleaching.

The Critical Window for Reversal

Reversal hinges on one factor more than any other: time.

If the stressful conditions subside within a few weeks—if the hot water cools down, the pollution dissipates—the coral has a chance. The zooxanthellae can slowly repopulate from the small number that remained or from free-floating algae in the water. The coral starts to feed itself again, regains its color, and recovers its health.

This natural recovery process isn't fast. It can take months, even years, for a coral to fully regain its pre-bleaching growth rates and reproductive capacity.

The problem we face now is that the stressful conditions aren't subsiding. Mass bleaching events are lasting longer and recurring more frequently, thanks to climate change. A reef might bleach, start to recover, and then get hit by another marine heatwave before it's fully regained strength. This is like asking someone to run a marathon while they're still recovering from pneumonia.

Prolonged bleaching leads to coral death. The polyp starves. Or, in its weakened state, it's easily killed by diseases.

Natural Recovery vs. Human Intervention

Reef recovery happens on a spectrum, from purely natural processes to highly technical human-led restoration.

| Recovery Pathway | How It Works | Best For / Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Recovery | Stressors subside. Corals slowly regain algae. Neighboring healthy reefs supply larvae that settle and grow. | Healthy, well-connected reef systems with strong fish populations to control algae. Useless if bleaching is severe/repeated or if no "baby coral" source remains. |

| Assisted Natural Recovery | Humans remove local stressors: create marine protected areas, improve water quality, control algal growth. | Giving natural processes the best possible chance. The most cost-effective large-scale strategy. Requires political/social will. |

| Active Restoration (e.g., Coral Gardening) | Growing coral fragments in nurseries, then transplanting them onto degraded reefs. | Jump-starting recovery in high-priority, small areas. Works for specific, fast-growing species. Labor-intensive, expensive, doesn't fix root causes. |

| Innovative Interventions | Cloud brightening, selective breeding for heat-tolerant corals, assisted evolution. | Experimental. Potential for future resilience but scale and ecological risks are major unanswered questions. |

Most marine biologists will tell you that our top priority must be the middle column: Assisted Natural Recovery. It's the foundation. No amount of coral planting will work if the water is too hot and polluted. We have to give reefs breathing room.

How Can We Help Corals Recover? Actionable Strategies

So what does "giving reefs breathing room" actually look like on the ground (or in the water)? It's a multi-layered approach.

1. Tackle the Global Driver: Climate Change

This is non-negotiable. Reducing carbon emissions to limit global warming to 1.5°C is the single biggest action for coral reef survival. Every fraction of a degree matters. While this is a global policy issue, individual choices and advocacy add up.

2. Aggressively Manage Local Stressors

This is where local communities, governments, and conservation groups can have a massive immediate impact. Think of it as emergency care for the reef.

Water Quality: Reducing nutrient pollution from agriculture and sewage is huge. Nutrients fuel algal blooms that smother corals and hinder recovery. Projects that treat wastewater and manage watersheds are critical.

Marine Protection: No-take zones and well-managed Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are proven recovery engines. They protect herbivorous fish like parrotfish and surgeonfish. Why does this matter? These fish are the lawnmowers of the reef. They graze on the algae that would otherwise overgrow and kill bleached, struggling corals. A reef with a healthy population of grazers has a much better shot at natural recovery. The data from places like the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is clear on this.

Responsible Tourism: If you visit a reef, choose operators with strong eco-certifications. Don't touch corals, don't stir up sediment, use mooring buoys instead of dropping anchor. Physical damage is an unnecessary stressor on a system already on the edge.

3. Strategic, Science-Based Active Restoration

This isn't about planting corals everywhere. It's a surgical tool. Groups like the Coral Restoration Foundation in Florida or the Australian Institute of Marine Science focus on:

Coral Nurseries: Growing fragments of resilient, fast-growing species (like staghorn coral) on underwater structures.

Outplanting: Transplanting nursery-grown corals onto degraded reefs to create new, genetically diverse patches of life. These patches can then spawn and help repopulate larger areas.

The goal isn't to rebuild the entire Great Barrier Reef by hand—that's impossible. The goal is to create "lifeboats"—pockets of resilience that can seed future recovery once conditions stabilize.

The Tough Realities and Future Outlook

Let's be brutally honest. Reversing bleaching gets harder every year. The frequency of events is outpacing the natural recovery time of reefs. We are likely looking at a future where coral communities look different—dominated by more heat-tolerant but often less structurally complex species.

One subtle mistake many optimistic reports make is equating "coral cover" with "reef health." A reef might regain some coral cover after a bleaching event, but if it's now dominated by just one or two weedy species, it's a degraded ecosystem. The intricate architecture that housed thousands of fish species is gone. The recovery is partial.

The work now is about triage and resilience. It's about saving as much genetic diversity as possible—the corals that survive bleaching events might hold the key to future adaptation. It's about protecting the reefs that are still relatively healthy (like some in the Coral Triangle) as climate refuges.

Reversing coral bleaching is possible, but it's not guaranteed. It requires us to act on both the global climate crisis and the local stressors, simultaneously and with urgency. The coral's ability to bounce back is astonishing, but it's not infinite. We're testing its limits. The window for action is still open, but it's closing fast. The choice isn't between despair and hope; it's between action and surrender.

Your comment