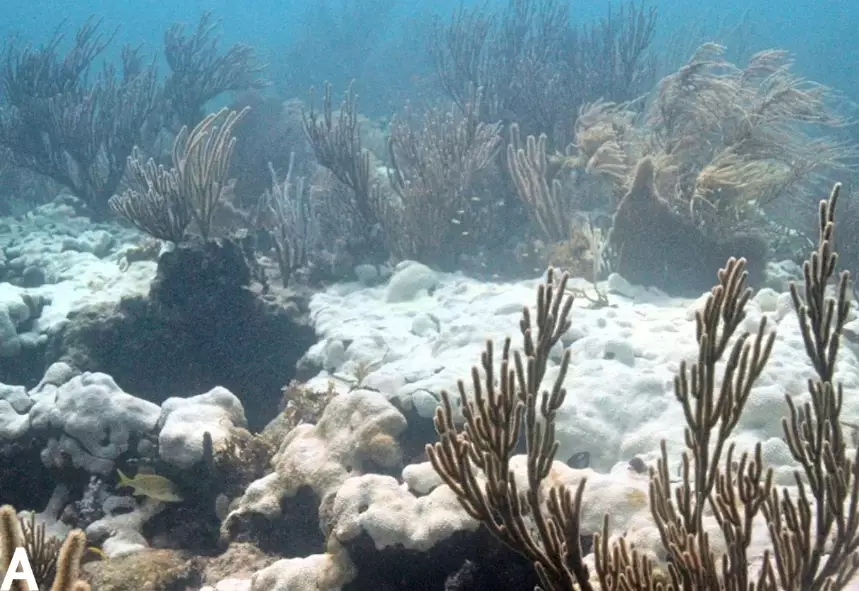

You've seen the photos. Vast stretches of reef that should be a riot of color look like a field of bone-white skeletons. Coral bleaching is the visual cry for help of an entire ecosystem in distress. But what's actually causing it? While the image of a bleached reef is simple, the sources of the stress are a tangled web. Most explanations stop at "warming seas," but that's only part of the story—and focusing solely on it can lead us to miss other critical, actionable problems.

After years of diving on reefs from the Caribbean to the Pacific, I've seen bleaching up close. It's not always uniform. Sometimes it's patchy, other times it follows a distinct depth line or affects certain coral species first. This variation is your first clue that there isn't one single villain. The stress comes from three primary directions, often working in combination to push corals past their breaking point.

Quick Navigation

Let's break down each of these sources of coral bleaching. Understanding them is the first step toward knowing how to protect what's left.

Source 1: The Heat is On – Elevated Sea Temperatures

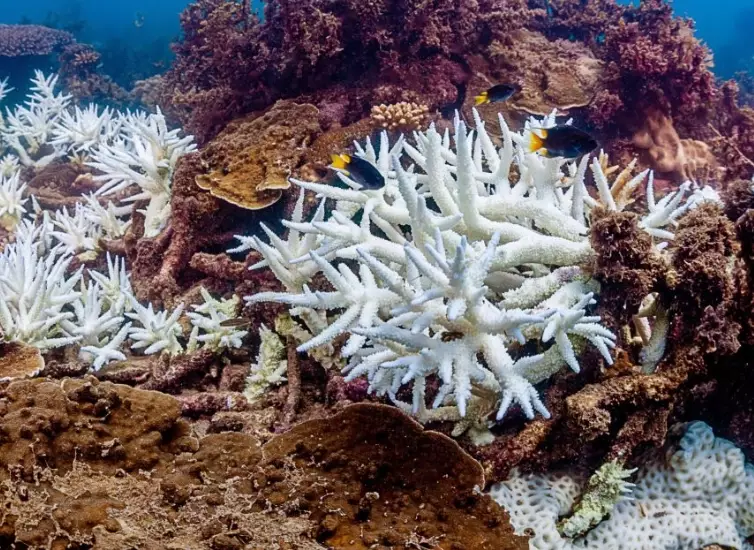

This is the big one, the global-scale driver. Corals have a narrow comfort zone, typically between 23°C and 29°C (73°F to 84°F). When water temperatures stay just 1-2°C above the usual summer maximum for a week or more, the symbiotic relationship breaks down.

Here’s what happens inside the coral. The microscopic algae (zooxanthellae) living in its tissues start producing toxic levels of reactive oxygen molecules under the heat stress. To save itself, the coral expels its algal partners. Since these algae provide up to 90% of the coral's food through photosynthesis and give it color, the coral turns white and begins to starve.

Key Point: It's not the absolute temperature that matters most, but the duration of the anomaly. A sharp, brief spike might cause minor stress. A sustained, slight increase is what triggers mass bleaching events. Tools like NOAA's Coral Reef Watch use this concept of "degree heating weeks" to predict and monitor bleaching.

Why This is More Than Just a "Hot Day"

The problem is the baseline is shifting. Ocean heatwaves are becoming more frequent, intense, and longer-lasting. Events like the 2016-2017 mass bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef, where an estimated 30% of corals died, are no longer rare. They're becoming the norm. Corals need years to recover from a severe bleaching event, but the gaps between events are shrinking. They're getting knocked down before they can get back up.

I remember diving in the Maldives after the 2016 event. The contrast was jarring. One side of a channel, somewhat protected by cooler upwelling, held vibrant life. The other side, fully exposed to the sustained warm water flow, was a ghost town. It was a perfect, heartbreaking illustration of how localized conditions interact with the global heat signal.

Source 2: Light and Toxins – Solar Radiation & Pollution

Heat rarely works alone. It's often partnered with intense sunlight, specifically ultraviolet (UV) radiation. High water temperatures make corals more susceptible to photodamage. Think of it like a bad sunburn—you're more likely to get one on a hot day, but the burn itself comes from the UV rays. During calm, clear weather (which often accompanies heatwaves), UV penetration is at its maximum, delivering a one-two punch of thermal and light stress.

Then there's the local stuff—the pollution and runoff from land. This is where individual communities and poor coastal management play a direct role. The main offenders here are:

- Freshwater Runoff: Heavy rains from storms or floods can dump a layer of freshwater onto near-shore reefs. Corals are marine animals; low salinity is a massive shock that can trigger immediate bleaching.

- Sediment: Deforestation and coastal construction send plumes of silt into the sea. This sediment settles on corals, smothering them and blocking the light their algae need. The coral spends energy trying to clean itself, energy it doesn't have to spare.

- Nutrient Pollution: Fertilizer runoff and sewage are packed with nitrogen and phosphorus. This doesn't directly bleach corals, but it fuels the growth of macroalgae (seaweed) that can outcompete and overgrow corals. It also encourages bacterial growth, which can lead to disease (see Source 3).

- Chemical Pollutants: Sunscreen chemicals like oxybenzone, along with pesticides and other toxins, can be directly toxic to corals and their symbiotic algae, disrupting their biology and making them more vulnerable to other stresses.

A common mistake is to overlook this source because it's less dramatic than a headline about ocean warming. But on many reefs, especially near populated coasts, pollution is the chronic stressor that lowers the coral's overall health, making it bleach at a lower temperature threshold. A resilient, clean reef can withstand more heat than a sickly, polluted one.

Source 3: Biological Attacks – Disease and Predators

This source is often the silent finisher. When corals are stressed by heat or pollution, their immune systems are compromised. This is when disease outbreaks can sweep through a population. Diseases like White Syndrome, Black Band Disease, and Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease cause rapid tissue loss, leaving behind bare white skeleton that is easily mistaken for bleaching.

The difference is in the pattern. Thermal bleaching usually affects large areas uniformly or following temperature contours. Disease often shows as distinct, spreading lesions or bands on an otherwise healthy-looking coral colony.

Then there are predators. The most notorious is the crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS). In outbreak numbers, these starfish can devour hectares of coral. They inject digestive enzymes, turning coral tissue into a soup they then ingest, leaving behind a stark white skeleton. Again, the result looks like bleaching, but the cause is direct consumption. COTS outbreaks themselves are often linked to the nutrient pollution mentioned earlier, which boosts plankton levels and increases larval starfish survival.

| Source of Stress | Primary Driver | Visual Clue | Typical Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated Temperature | Climate Change / Ocean Heatwaves | Uniform whitening, often starting on upper surfaces & branching tips. | Regional to Global (Mass Events) |

| Solar Radiation & Pollution | Local Weather & Land-Based Runoff | May be patchier; sediment visible on corals; algae overgrowth nearby. | Local to Regional |

| Disease & Predation | Biological Agents (Bacteria, Starfish) | Spreading lesions, spots, or bands (disease); starfish present (predation). | Local, but can spread |

The takeaway? When you see a white coral, don't just blame the heat. Look closer. Is the water murky? Are there starfish nearby? Is the bleaching pattern strange? The answer informs the solution. Global warming requires global action. Pollution requires local governance and better practices. Disease and predator outbreaks require targeted management.

Your Coral Bleaching Questions Answered

Let's tackle some of the specific questions I hear most often from divers, snorkelers, and concerned ocean lovers.

Understanding the three sources of coral bleaching—heat, light/pollution, and biological attacks—moves us past simple fear into informed action. It shows that while the climate battle is paramount, there are immediate, local fights we can win to give these incredible ecosystems a better shot at survival. The next time you see an image of a bleached reef, you'll see more than just white coral. You'll see a complex story of stress, and hopefully, a roadmap for where to focus our efforts.

Your comment