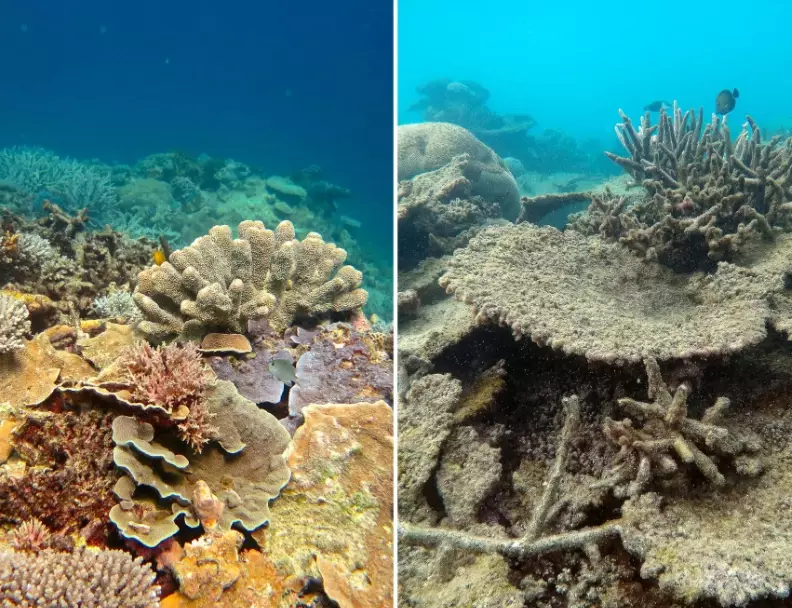

Right now, as you read this, a massive, silent catastrophe is unfolding underwater. We are in the thick of the fourth global coral bleaching event on record. It's not a future threat or a localized problem. It's a present-tense, planet-wide emergency. The short, brutal answer to "how bad is it?" is this: worse than it's ever been, and accelerating. I've been diving for over a decade, and the changes I've seen in the last five years alone are enough to make your heart sink. Reefs that were technicolor wonderlands are now pale, ghostly landscapes. This isn't just about losing pretty fish; it's about the collapse of an entire ecosystem that supports a quarter of all marine life and hundreds of millions of people.

Your Guide to the Coral Crisis

What is Happening: The Fourth Global Bleaching Event

Let's cut through the jargon. Coral bleaching happens when corals get stressed, usually by high water temperatures. They expel the tiny, colorful algae (zooxanthellae) that live in their tissues and provide them with up to 90% of their food. Without these algae, the coral's white skeleton shows through—they look "bleached." They're not dead yet, but they're starving.

A "global bleaching event" is declared by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) when significant bleaching is reported across all three major ocean basins (Atlantic, Pacific, Indian) over a one-year period. We've only had three before this: 1998, 2010, and 2014-2017. The current event, announced in April 2024, is notable for its sheer scale and intensity.

What makes this event particularly alarming is its geographic spread and the types of reefs being hit. We're seeing severe bleaching in regions previously considered more resilient or less frequently impacted.

The Bleaching Scale: From Stress to Death

Not all bleaching is equal. Scientists use a scale to categorize severity, and understanding this is crucial to grasping the real-world impact. It's not a binary of "colored" or "white."

| Alert Level (NOAA) | What It Looks Like | Likely Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Watch | Minor paling, maybe 10-30% of corals affected. You might not even notice as a casual observer. | Most corals will recover if stress is brief. |

| Warning | Widespread, obvious paling. 30-60% of corals bleached. The reef looks "washed out." | Significant stress. Some mortality of sensitive species expected. |

| Alert Level 1 | Severe, widespread bleaching. >60% of corals bleached. The ghostly white is unmistakable. | High mortality likely. Recovery will take years, if it happens at all. |

| Alert Level 2 | As above, but with significant coral mortality already observed. | Catastrophic mortality. Reef structure and function are severely compromised. |

Right now, vast swathes of the tropics are at Alert Level 1 or 2. That's the critical detail. We're not just in a "watch" phase; we're in the mass mortality phase across multiple regions simultaneously.

Ground Zero: The Hardest-Hit Locations Right Now

This isn't abstract. The crisis has specific addresses. Here’s where the situation is most dire, based on reports from NOAA's Coral Reef Watch and networks like the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI).

The Great Barrier Reef, Australia

The world's largest reef system is suffering its fifth mass bleaching event in eight years. The southern third, which had largely escaped the worst of previous events, is now experiencing unprecedented bleaching. Aerial surveys confirm widespread, severe damage. The cumulative impact of so many events in such a short time is the real story—reefs have no time to recover.

The Wider Caribbean & Florida

From the Bahamas down to the Grenadines, heat stress has been off the charts. Florida's coral reef tract experienced potentially the most severe thermal stress ever recorded in the summer of 2023. Coral restoration nurseries, where scientists grow and outplant corals, became emergency triage units. They had to physically move thousands of coral fragments into cooler, land-based tanks to save them.

The Eastern Tropical Pacific

Reefs in Panama, Costa Rica, and around the Galápagos Islands are being hammered. These reefs are smaller and often less studied, but they are vital for local fisheries and biodiversity. The loss here is a quiet catastrophe.

Even more troubling are reports from the Red Sea and parts of the Indian Ocean, which have historically been more heat-tolerant. They are now showing signs of significant stress.

How Does Coral Bleaching Affect Diving?

If you're a diver, this hits home. The experience changes fundamentally.

The Visual Loss: It's depressing. The riot of color that defines a healthy reef vanishes. Fish populations that rely on coral for food and shelter begin to dwindle. The dive shifts from awe to a somber inventory of loss.

Economic Impact: Dive tourism in places like Thailand, the Maldives, or the Caribbean is a major economic driver. Bleached reefs lead to cancelled trips, lost income for guides and operators, and long-term reputational damage for a destination. I've spoken to shop owners in Southeast Asia who say clients are now asking, "Is the reef still colorful?" before they book.

A New Kind of Dive: Some operators are pivoting to "monitoring dives" where trained recreational divers help collect data on bleaching severity. It turns a disheartening sight into purposeful citizen science. It's a small silver lining, but an important one.

What Can Actually Be Done? Moving Beyond Hopelessness

The scale is overwhelming, but surrender isn't an option. Action happens on two fronts: global and local.

The Global Imperative (The Big One): Slash greenhouse gas emissions. This is non-negotiable. No amount of local conservation can save reefs if the water keeps heating up. Support policies and leaders committed to climate action. It's the most critical thing anyone can do.

Local & Personal Actions (The Essential Support):

- Be a Conscientious Diver/Snorkeler: Perfect your buoyancy. Never touch. Choose operators with strong environmental policies (mooring buoys, not anchors).

- Pressure the Industry: Ask your dive resort what they are doing to reduce their footprint, support local marine parks, and educate guests.

- Support Real Conservation: Donate to or volunteer with organizations doing hands-on reef restoration and science, like the Coral Restoration Foundation or local marine park authorities. Be wary of vague "coral planting" tourist experiences that may do more harm than good.

- Mind Your Sunscreen: Use mineral-based, reef-safe sunscreen (zinc oxide/titanium dioxide). The data on chemical oxybenzone harming corals and bleaching is convincing enough to warrant the switch.

The goal isn't to return reefs to some mythical past state. It's to buy them time, reduce all other stresses (pollution, overfishing), and create the conditions for them to adapt—if we can rapidly cool the planet down.

Your Burning Questions Answered

The situation is bad. Historically bad. But understanding the precise nature of the crisis—the scale, the locations, the mechanisms—is the first step away from paralysis. It moves us from a vague feeling of concern to a clear-eyed recognition of what's at stake and where to focus our efforts. The reefs are sending a desperate distress signal. The question is whether we're listening closely enough to understand it and act before the static of inaction drowns it out completely.

Your comment