I remember the first time I dove Molasses Reef in Key Largo over a decade ago. It was a sensory overload of color and life—schools of blue tang, towering elkhorn corals that looked like antlers, the constant chatter of parrotfish. Last summer, I went back. The silence hit me first. Then the color, or lack of it. Vast stretches looked like a ghost town, coated in a sickly brown algae. The iconic structures were still there, but they were skeletons. This isn't just an anecdote. It's the lived reality of the Florida Coral Reef, the only living coral barrier reef in the continental U.S., and it's in the fight of its life.

The term "dying" feels dramatic, but it's accurate. We're not talking about a slow decline anymore. We're witnessing a rapid, mass mortality event driven by a perfect storm of climate change and disease. For divers, ocean lovers, Floridians, or anyone who cares about the planet, understanding this crisis is the first step toward action.

What You'll Find in This Guide

What's Actually Happening to the Reef? (It's More Than Bleaching)

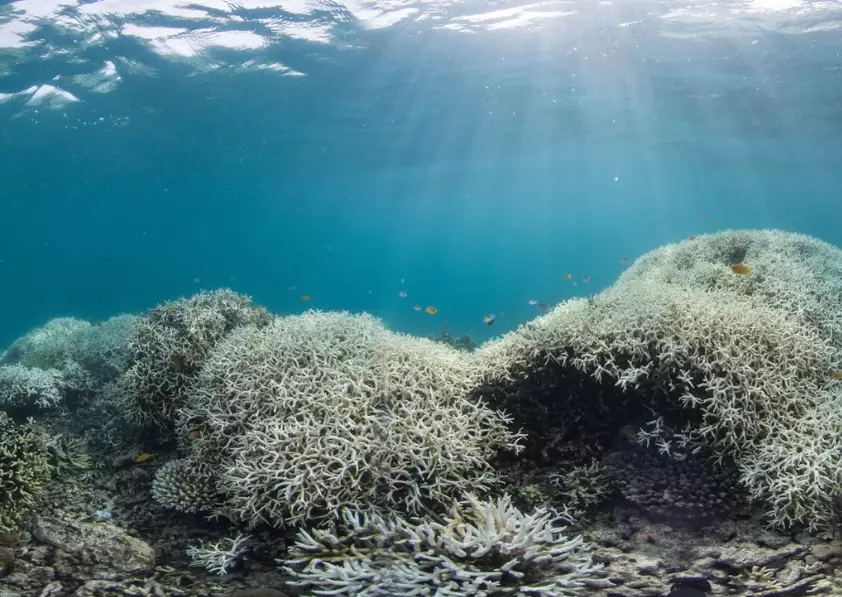

You've probably heard of "coral bleaching." It's when stressed corals expel the tiny, colorful algae (zooxanthellae) that live in their tissues and provide them with 90% of their food. The coral turns bone white. It's starving, but not dead yet. If the stress—usually high water temperature—passes quickly, the algae can return.

Florida's problem is that the stress isn't passing. The summers of 2023 and 2024 saw prolonged marine heatwaves with water temperatures consistently hitting 90°F (32°C) and above, far beyond the corals' tolerance. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared a Level 2 (the highest) bleaching alert. This wasn't a typical bleaching event; it was catastrophic.

But bleaching is just the opening act. The main killer is a fast-moving, lethal disease called Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD). First identified near Miami in 2014, it's like a flesh-eating bacteria for coral. It spreads rapidly, killing entire colonies within weeks. A coral weakened by heat stress has no chance against SCTLD. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission tracks its relentless spread down the reef tract. The combination is devastating: the heatwave weakens the entire population, and the disease mows them down.

The Hard Numbers: Some reefs in the Lower Keys have seen near-total mortality of reef-building corals like elkhorn and staghorn. In monitored sites, live coral cover—the percentage of the reef made of living coral—has plummeted from historical averages of 20-30% to single digits in many areas. We're losing decades of growth in a single season.

Why Should You Care? It's Not Just About Fish

If you're not a diver, it's easy to think this is a niche environmental issue. It's not. This reef is a critical piece of infrastructure.

Economic Engine: The Florida Reef Tract generates over $6 billion in annual economic activity and supports 71,000 jobs through tourism, recreation, and fishing. The collapse of the reef means lost livelihoods for captains, dive shops, hotels, and restaurants across the Keys.

Storm Protection: Those complex coral structures break wave energy. They are Florida's first line of defense against hurricanes and storm surges. A degraded reef means more expensive coastal damage, higher insurance premiums, and greater risk for coastal communities. A study by the U.S. Geological Survey and others quantifies this buffer effect, and its loss is a direct threat to property and safety.

Biodiversity Hotspot: Although it covers less than 1% of the ocean floor, the reef is home to 25% of all marine species. It's a nursery for commercially important fish like grouper and snapper. Lose the reef, and you collapse the entire local marine food web.

The Root Causes: A Breakdown of the Killers

Pointing fingers at just one cause is a mistake. It's a layered crisis.

The Climate Hammer: Ocean Warming and Acidification

This is the overarching threat. Burning fossil fuels pumps greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which traps heat. Over 90% of that excess heat is absorbed by the ocean. The result is longer, more intense marine heatwaves. Corals have a narrow temperature range. We're pushing them past it every summer.

A related, slower-moving threat is ocean acidification. As the ocean absorbs excess CO2, the water becomes more acidic, making it harder for corals to build their calcium carbonate skeletons. They grow slower and become more fragile.

The Deadly Disease: SCTLD

The origins of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease are still being studied, but it's now one of the worst coral disease outbreaks on record globally. It affects over 20 coral species, including primary reef-builders. Its transmission is not fully understood but is likely through water movement and direct contact. There is no known cure in the wild.

Local Stressors: The Final Straw

While climate change is the global sledgehammer, local problems add unbearable stress. These include:

- Water Pollution: Runoff from Florida's coasts carries fertilizers, sewage, and sediments. This nutrient pollution fuels algal blooms that smother corals and block sunlight.

- Physical Damage: From careless boat anchors and groundings to unsustainable fishing practices.

Think of it this way: a coral struggling with poor water quality is like a person with a weak immune system. When the climate heatwave hits (like a pandemic), they're the first and hardest to fall.

What's Being Done? The Race to Restore

All hope is not lost. Scientists and conservationists are engaged in a massive, unprecedented effort that feels part science, part battlefield triage.

1. Coral Rescue and Nurseries: Groups like the Coral Restoration Foundation are doing the frontline work. They collect genetic fragments from healthy corals before disease hits an area. They grow these "corals of hope" in offshore and land-based nurseries. In 2023, they had to perform emergency evacuations of nursery corals to land-based tanks to save them from the heat.

2. Assisted Evolution and Selective Breeding: Researchers are identifying the rare corals that survive bleaching or resist disease. They're selectively breeding these resilient individuals to create a new generation of "super corals" better adapted to warmer waters. The Florida Aquarium made headlines by successfully spawning Atlantic pillar coral in a lab for the first time, a breakthrough for genetic banking.

3. Large-Scale Outplanting: Once corals are grown to a viable size, divers literally epoxy them back onto the reef. It's labor-intensive, expensive, and scale is a huge challenge. But thousands of corals are outplanted every year.

| Coral Species | Status | Restoration Focus | Recovery Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elkhorn Coral | Critically Endangered | High - Primary nursery species | Medium-High (fast grower) |

| Staghorn Coral | Critically Endangered | High - Primary nursery species | Medium-High (fast grower) |

| Pillar Coral | Critically Endangered | Very High - Now reliant on lab spawning | Low (very slow grower) |

| Brain & Star Corals | Severely Depleted | Medium - Targeted for SCTLD treatment | Low-Medium (slow growing) |

The reality? Restoration is buying time. It's a stopgap to preserve genetic diversity and reef function while the world (hopefully) tackles the root cause: climate change.

How You Can Actually Help (Practical Steps for Everyone)

Feeling overwhelmed is normal. But feeling helpless is a choice. Here are concrete actions with real impact.

For Divers & Snorkelers Visiting Florida:

- Choose a Blue Star Operator: This NOAA-led program recognizes operators committed to sustainable practices. They provide buoyancy control briefings, use mooring buoys instead of anchoring, and educate guests.

- Master Your Buoyancy: Seriously. Hover. A silty kick onto a newly outplanted coral can kill it. Practice in a pool first.

- Use Reef-Safe Sunscreen: This is non-negotiable. Avoid oxybenzone and octinoxate. Use mineral-based sunscreens with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. Many shops in the Keys won't let you board without it.

- Don't Touch. Ever. The oils on your skin can harm corals, and their polyps are fragile.

For Anyone, Anywhere:

- Reduce Your Carbon Footprint: Advocate for and support the transition to clean energy. This is the single most important long-term action.

- Support the Organizations on the Ground: Donate to or volunteer with the Coral Restoration Foundation, Mote Marine Laboratory's coral program, or the Florida Aquarium's conservation fund.

- Vote and Advocate: Support policies and leaders that address climate change, protect water quality, and fund coral science.

- Spread the Word, Not the Despair: Share stories of the restoration work, not just the doom. Hope drives action.

The Future of Diving in Florida

Diving the Florida Reef will be different. You will see more algae, more dead structure, and fewer fish in some places. It can be heartbreaking.

But you'll also see something new: the work. You might dive near a coral nursery, a "tree" of growing coral fragments. You might see clusters of outplanted corals, tagged and monitored. The narrative shifts from "consumptive tourism" to "participatory witness." The best dive operators are now educators and conservation partners.

Is it worth it? Absolutely. You're not just seeing an ecosystem; you're seeing an ecosystem under intensive care, and the dedicated team trying to save it. That is a powerful, humbling, and ultimately hopeful story to be part of.

Your comment