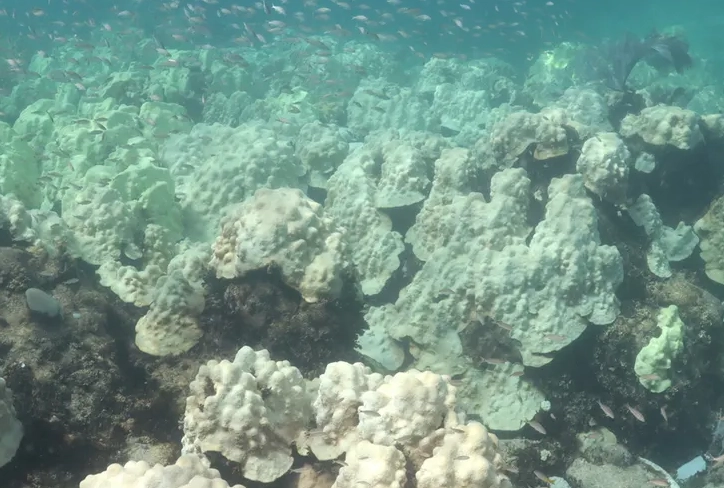

You've seen the photos. Ghostly white corals standing where vibrant gardens of color once thrived. The term "Florida Keys coral bleaching" isn't just a scientific headline; it's a reality that's reshaping the underwater landscape of one of the world's most famous dive destinations. If you're planning a trip to Key Largo, Islamorada, or Marathon, you need to know what's happening, what it means for your experience, and—most importantly—how you can be part of the solution, not the problem. Let's cut through the noise and get to the heart of the matter.

What You'll Find in This Guide

What Exactly Is Coral Bleaching?

First, a crucial correction: a bleached coral is not a dead coral. It's a severely stressed one. Think of it like a person with a high fever.

Corals are animals that live in a symbiotic partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live inside the coral's tissue, give it its spectacular colors (browns, greens, blues), and—through photosynthesis—provide up to 90% of the coral's energy. When the coral gets stressed, primarily by prolonged elevated water temperature, this partnership breaks down. The coral expels its algal tenants. Without the algae, the coral's white skeleton becomes visible through its transparent tissue. Hence, it looks "bleached."

Now, here's the subtle error most explanations miss: the coral isn't immediately starving. It can still feed on plankton using its stinging tentacles. But it's running on emergency reserves. If the stress (high temperatures) subsides quickly enough—within a few weeks—the algae can move back in, and the coral can recover. If the stress lasts for months, or if other stressors like pollution or physical damage pile on, the coral will eventually die from disease or starvation. Then, algae and sponges take over the skeleton.

The Bottom Line: Bleaching is a distress signal, not an obituary. The window for recovery is real but narrow. This is why our actions during a bleaching event are so critical.

How Widespread Is Coral Bleaching in the Florida Keys?

The Florida Keys have been a global hotspot for bleaching events. The situation is dynamic, but data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and local monitoring groups like the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary tells a clear story. Mass bleaching events are becoming more frequent, more severe, and longer-lasting.

Let's break it down by area, because not all reefs are affected equally at the same time.

| Region of the Florida Keys | Typical Bleaching Vulnerability & Recent Trends | What Divers Might See |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Keys (Key Largo, Tavernier) e.g., John Pennekamp Park, Molasses Reef |

Very High. Shallow reefs close to shore heat up quickly. These are often the first and hardest hit. | Widespread paling or bleaching on shallow elkhorn and staghorn corals. Deeper reefs (60+ ft) may show more color but are not immune. |

| Middle Keys (Marathon, Duck Key) e.g., Sombrero Reef, Coffins Patch |

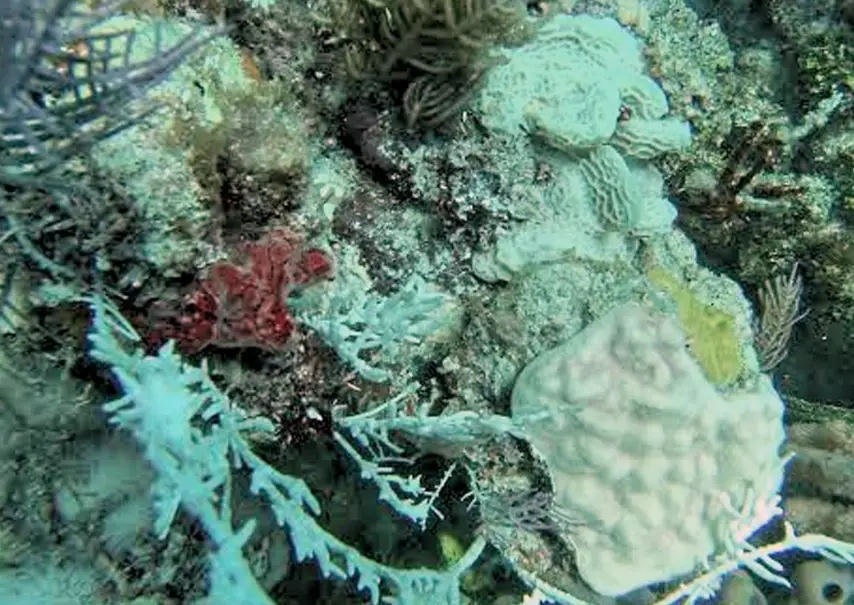

High to Moderate. Exposure to open ocean currents can sometimes provide slight relief, but not enough during major heatwaves. | Patchy bleaching. You might see healthy coral heads right next to completely white ones. A mixed and sobering scene. |

| Lower Keys (Big Pine Key, Key West) e.g., Looe Key, Sand Key |

Moderate to High. These reefs can benefit from deeper, cooler water from the Gulf Stream, but the 2023 event showed severe impact here too. | Historically resilient sites like Looe Key have shown significant bleaching recently, indicating the severity of modern heat stress. |

The summer of 2023 was a particularly brutal example. Satellite data showed sea surface temperatures around the Keys were consistently 2-3°C (up to 5°F) above normal for weeks. In some shallow areas, in-water thermometers hit 90°F+ (32°C+). The result was one of the most severe and spatially extensive bleaching events ever recorded in the region.

How Does Bleaching Affect Your Florida Keys Dive Trip?

Okay, so the science is grim. But what does this mean for you, packing your bags and your dive gear?

1. The Visual Impact: The reef will look different. There's no sugarcoating it. The dazzling, postcard-perfect colors will be muted. You'll see more white, more pale brown, more monotone landscapes. It can be emotionally tough for first-timers and veterans alike.

2. The Marine Life: Here's a bit of good news: the fish don't just disappear. Parrotfish, angelfish, grunts, snappers, barracuda, and nurse sharks are all still there. The reef's structure still provides habitat. But the long-term health of that fish community depends on the coral's survival. If corals die, the complex structure erodes over years, and fish diversity declines.

3. The Dive Experience: Responsible dive operators will adjust. They might choose deeper sites where bleaching is less severe. Their briefings will heavily emphasize perfect buoyancy and no touching. The focus of the dive may shift slightly—from "look at all the coral" to "look at this amazing biodiversity the coral structure supports, and let's not harm it."

I remember a dive at Molasses Reef after a minor bleaching event. My guide, a local with 20 years on that reef, pointed to a large, white brain coral. "See that? It's bleached, but look closer." He showed us tiny polyps still extended, feeding at night. "It's fighting. Our job is to not make its fight harder." That reframed the entire dive for me.

What Can You Do About It? A Practical Action Plan

This is where you move from observer to participant. Your choices directly impact the reef's chance to recover.

Choose Your Operator Like an Environmentalist

Don't just book the cheapest trip. Ask questions. A truly sustainable operator will:

- Give a conservation-focused briefing: They should spend real time on buoyancy, no-touch rules, and fin awareness over coral.

- Mandate reef-safe sunscreen: Not just "recommend" it. Chemicals like oxybenzone and octinoxate are proven stressors. Mineral-based zinc oxide is the gold standard.

- Have a clear stance on gloves: Many top conservation operators now ban gloves for recreational divers. It removes the temptation to grab or steady yourself on the reef.

- Support local science: Do they donate to or partner with Mote Marine Laboratory's coral restoration work? Do they participate in citizen science data collection?

Master Your Diving Skills Before You Go

If your buoyancy is shaky in a quarry or lake, it will be a liability on a stressed reef. Practice in a pool. Do a buoyancy-focused refresher. Consider wearing less weight. The goal is to hover without moving your fins near the bottom. This isn't just about skill pride; it's about survival for the coral below you.

Rethink Your Kit

- Sunscreen: Switch to a certified reef-safe, mineral-based formula before your trip. Apply it at least 15 minutes before entering the water to let it bind to your skin.

- Better than sunscreen: A long-sleeved rash guard or dive skin. Sun protection that can't wash off.

- Camera: Use a floaty grip or wrist strap. A dropped camera crashing into coral is a disaster.

The Non-Consensus Tip: Everyone says "don't touch." But few mention that even the tiny vortex from a fin kick can blast sediment onto a coral, smothering it. Practice frog kicks and helicopter turns away from the reef. Your fin tips should never point downward when you're near the bottom.

Advocate and Donate

Your voice and wallet matter back home. Support organizations doing the hard restoration work directly in the Keys, like the Mote Marine Laboratory's Coral Reef Restoration Program or the Coral Restoration Foundation. These groups grow resilient corals in nurseries and outplant them onto damaged reefs. It's a tangible, hopeful action.

Your Coral Bleaching Questions Answered

What are the best and worst times of year to see coral bleaching in the Florida Keys?

If I see bleached coral while diving in the Keys, should I avoid touching it?

How can I find a dive operator in the Florida Keys that prioritizes reef conservation?

Are some reefs in the Florida Keys more resilient to bleaching than others?

Visiting the Florida Keys during a time of coral bleaching requires a shift in perspective. It's not just a vacation; it's a chance to witness a critical environmental moment and to dive with purpose. The reefs need responsible tourists now more than ever. By choosing wisely, diving skillfully, and supporting restoration, you become part of the story of resilience, not just the story of loss. The color may be fading in some places, but the need for passionate, informed stewards has never been brighter.

Your comment