Let's cut to the chase. Is coral bleaching bad for the environment? It's not just bad. It's catastrophic. Framing it as merely 'bad' is like calling a house fire 'inconvenient'. When corals bleach and die, they don't just take their pretty colors with them. They trigger a domino effect that unravels entire marine ecosystems, cripples coastal economies, and strips away a critical line of defense for millions of people. This isn't a distant problem for scientists to worry about. It's a here-and-now crisis with teeth.

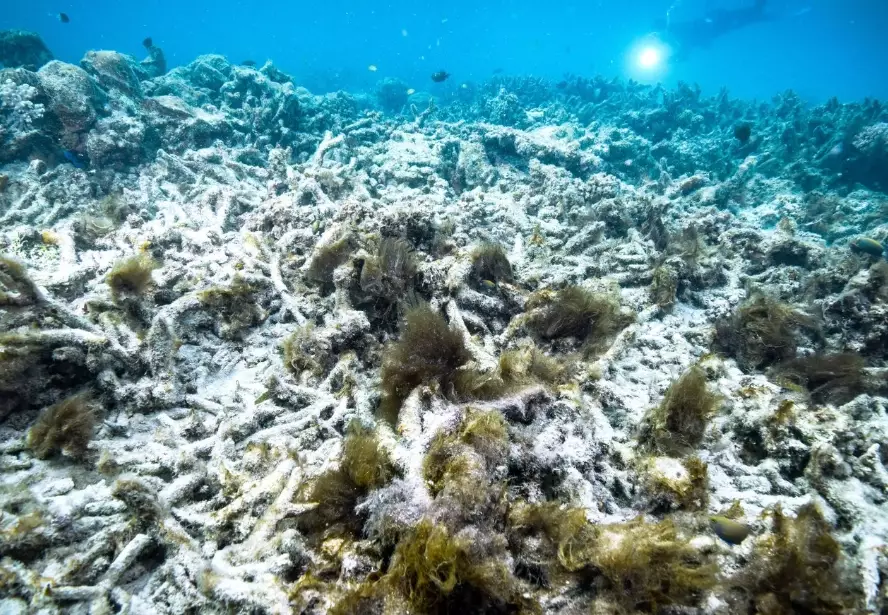

I've seen it firsthand. Diving on reefs that were vibrant labyrinths of life a decade ago, now reduced to silent, gray fields of bone. The silence is the worst part. No clicks, no pops, just the hollow sound of your own breathing. It feels wrong.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

The Ecological Unraveling: It's Not Just About the Corals

Think of a coral reef as a bustling underwater city. The corals are the apartment buildings. Inside them live microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae are the tenants who pay their rent in the form of food (sugars from photosynthesis), which gives the coral its color and up to 90% of its energy.

Coral bleaching is an eviction notice. When stressed by high water temperatures, pollution, or ocean acidification, the coral expels its colorful algal tenants. The coral tissue turns transparent, revealing the stark white skeleton beneath. It's not dead yet, but it's starving.

If the stress is brief, algae can move back in. But if it lasts weeks, the coral dies. And when the 'apartment building' collapses, every resident is made homeless.

The Domino Effect of a Dead Reef

This is where the true environmental damage cascades. The loss of complex coral structure has immediate and severe consequences for marine biodiversity:

The Food Web Collapses. Countless species, from tiny shrimp to parrotfish, rely directly on corals for food and shelter. Lose the corals, and you lose the foundation of the food chain. Herbivorous fish that keep algae in check disappear. Then, the algae smother any remaining coral, preventing recovery. Predators like reef sharks and groupers, with nothing to eat, move on or starve.

It's a silent, rapid unraveling. A study following the 2016 mass coral bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef found a drastic decline in the abundance and diversity of fish communities. The reef didn't just get quieter; its entire social and economic fabric dissolved.

Back-to-back marine heatwaves bleached over two-thirds of the world's largest reef system. On some northern sections, up to 50% of the corals died. The scale was unprecedented. This single event transformed vast swathes of complex, three-dimensional habitat into flat, barren rubble. The recovery, experts estimate, will take decades—if another heatwave doesn't hit first.

It's not just about the fish we see. Sponges, worms, and other cryptic critters that form the base of the food web vanish. The reef's natural nutrient recycling system breaks down. The ocean's productivity in that area plummets.

The Economic Aftermath: When the Reef Stops Paying

Reefs aren't just ecological wonders; they are economic powerhouses. Their death has a direct, painful price tag for human communities.

Tourism and Fisheries Take a Direct Hit. Imagine being a dive shop owner in the Caribbean or Southeast Asia. Your entire business is built on the allure of colorful reefs. When they bleach and turn white, tourists cancel. They go elsewhere. Livelihoods evaporate overnight.

The same goes for fisheries. Reefs are nurseries for an estimated 25% of all marine fish species. Commercially vital species like snapper, grouper, and lobster depend on them. A dead reef means smaller catches, lost income, and increased food insecurity for coastal communities that rely on fish as a primary protein source.

The global value of coral reefs for tourism and fisheries is estimated in the tens of billions of dollars annually. That revenue stream dries up with the corals.

The Silent Storm: Loss of Coastal Protection

This is perhaps the most underrated and dangerous consequence. Healthy coral reefs act as natural, self-repairing breakwaters. They dissipate up to 97% of wave energy before it hits the shore.

When a reef dies and its structure crumbles from erosion and bioerosion, that protective barrier vanishes. The result?

- Increased coastal erosion: Beaches that tourists love simply wash away.

- Heightened flood risk: Storm surges from hurricanes and cyclones penetrate much farther inland.

- Saltwater intrusion: Flooding contaminates freshwater aquifers, threatening drinking water and agriculture.

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami provided tragic, real-world data. Areas located behind healthy, wide reefs suffered significantly less damage and fewer deaths than areas where the reefs were degraded or absent. A dead reef isn't just an ecological loss; it's a removed shield for millions of people.

Replacing this lost protection with artificial seawalls is astronomically expensive and often ecologically damaging itself. The reef provided this service for free.

Moving Beyond Grief to Action: What Actually Works?

Okay, the picture is grim. But despair isn't a strategy. The question shifts from "Is it bad?" to "What can we do about it?" The solutions exist on a spectrum, from global to hyper-local.

The Non-Negotiables: Global and Systemic Action

This is the big one. The primary driver of mass bleaching is climate change-induced ocean warming. No amount of local action can save reefs if the water keeps getting hotter. Rapid, deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions are the single most important thing for the long-term survival of coral reefs. Supporting policies and leaders committed to this is paramount.

Simultaneously, we must slash the other major stressors: nutrient pollution from agricultural runoff and sewage, and destructive overfishing. These local pressures weaken reefs, making them far more likely to bleach when a heatwave hits.

Your Direct Toolkit: Actions That Make a Difference

As an individual, your power lies in your choices. Feeling helpless is optional.

1. Be a Conscious Consumer.

This is your biggest lever.

Travel: Choose dive operators and resorts with genuine conservation credentials. Do they use mooring buoys instead of dropping anchors? Do they cap guest numbers? Do they fund local reef restoration projects? Your wallet votes.

Seafood: Use guides from the Marine Stewardship Council or Seafood Watch to avoid species caught with destructive methods or from overfished stocks.

Sunscreen: This is a no-brainer. Use mineral-based, "reef-safe" sunscreens with non-nano zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. Avoid oxybenzone and octinoxate, which are proven to harm coral larvae and increase bleaching susceptibility.

2. Support the Right Organizations.

Donate to or volunteer with groups doing on-the-ground, science-based work. Look for organizations focused on:

- Restoration: Growing and outplanting resilient corals (e.g., Coral Restoration Foundation).

- Advocacy: Fighting for marine protected areas and stronger environmental policies.

- Science: Researching heat-resistant "super corals" and assisted evolution.

3. Reduce Your Own Footprint.

Everything that reduces your carbon and pollution output helps. Energy efficiency at home, reducing plastic use (which often becomes marine debris), mindful consumption, and supporting clean energy all contribute to the systemic change reefs need.

Reefs are resilient. They've bounced back from disturbances before. But the pace and intensity of today's threats are unprecedented. They need a break. They need cooler water, cleaner water, and space to recover. We are the only ones who can provide that.

The story isn't over. But the next chapter depends entirely on the choices we make now. It's not about saving the reefs for their beauty alone; it's about preserving the fundamental life-support systems they provide for countless species, including our own.

Your Coral Bleaching Questions, Answered

What is the main cause of coral bleaching that most people overlook?

How long does it take for a bleached coral reef to recover?

As a diver or tourist, what is the single most effective action I can take to help?

Can coral reefs adapt to warmer temperatures fast enough?

Your comment